Plaats een aanvulling

POWER FOR FREEDOM

Wanneer: 13/08/2018 - 14:58

POWER FOR FREEDOM.

TOGETHER WE ARE STRONG !

article from the Guardian.

current edition:

International edition

The Guardian - Back to home

‘Intoxicating freedom, gripping fear’: Mumia Abu-Jamal on life as a Black Panther

Black power behind bars

Black Panther

The best known of all incarcerated black radicals speaks out in a two-year email correspondence with Ed Pilkington on the ‘continuum’ of the Black Panthers to Black Lives Matter

Ed Pilkington

@edpilkington

Mon 30 Jul 2018 09.00 BST

Last modified on Mon 30 Jul 2018 13.09 BST

Shares

1,078

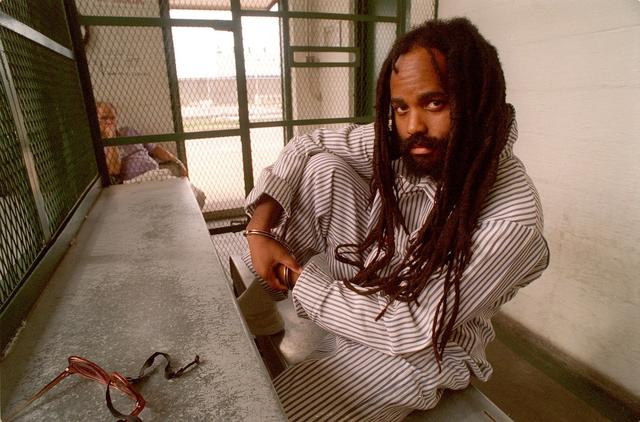

Former Black Panther Mumia Abu-Jamal. Photograph: April Saul/Philadelphia Inquirer

T

he letter was dated 30 August 2016. Written in black ink in spidery, meticulous handwriting, it proclaimed at the top of the page: “On a Move!”, the mantra of the Move group of black liberationists from Philadelphia who clashed violently with the city’s police force 40 years ago, sending nine of them to prison for decades.

The author was Mumia Abu-Jamal, who is the closest thing that exists today to an imprisoned Black Panther celebrity. He joined the Black Panther party in the 1960s when he was just 14, and later became a prominent advocate for the Move organization.

For the past 36 years he has been incarcerated in Pennsylvania prisons, including two decades spent on death row, having been convicted of murdering a police officer at a Philadelphia street corner in 1981. His case has reverberated around the world, inspiring admiration and opprobrium in equal measure, in what has become a global cause-celebre.

As such, he could be regarded as the figurehead of the cadre of imprisoned African-American militants who are still behind bars today. Collectively they amount to the unfinished business of the 1970s black liberation struggle, as they languish still in prison in some cases almost half a century after they went in.

By the Guardian’s count, there are 19 of them, two women included. That headcount is very slowly being diminished, as the debate around whether they have earned their freedom grows more intense with every passing year.

Last week one of Abu-Jamal’s peers, Robert Seth Hayes, was released from a New York maximum security prison on parole having served 45 years for the murder of a city transit officer.

I had sent that initial letter to Abu-Jamal to ask his views about Albert Woodfox, a former Black Panther from Louisiana who had been held in solitary confinement in a 6ft by 9ft concrete box for 43 years until his release a few months earlier.

In my opening letter to Abu-Jamal, I’d mentioned that the warden of Angola penitentiary in the 1990s, Burl Cain, had tried to justify keeping Woodfox in total isolation for four decades because of the prisoner’s commitment to “Black Pantherism”.

Advertisement

Abu-Jamal, 64, found that expression very diverting, judging by his response. Until Woodfox’s “illegal and unjust imprisonment,” he wrote back, “I had never heard nor read of the so-called crime of ‘Black Pantherism’! Leave it to the prisoncrats of Angola to actually coin the term!”

Pinterest

A supporter of inmate Mumia Abu-Jamal outside City Hall in Philadelphia, in 2006. Photograph: Jeff Fusco/Getty Images

Then Abu-Jamal did something that was to become familiar to me over the ensuing months. He took that one comment of a Louisiana prison warden and riffed off it to create an entire social theory of modern American society.

“As we see from the obscene and unprecedented mass incarceration of Black people,” he wrote, “‘Black Pantherism’ is but a synonym for Blackness itself. For in a society deeply imbued with white supremacy, Blackness is itself a crime.”

Abu-Jamal spent 20 years on death row and during that time concerns about the fairness of his death sentence drew international attention. Amnesty International took up his cause, the New York Times crowned him the “world’s best known death-row inmate” and a Paris street was named after him. Among the movie stars, writers and intellectuals who protested on his behalf were Paul Newman, Alice Walker, Salman Rushdie and Noam Chomsky.

As impressive as the high-profile support he attracted over the years was the vitriol he inspired in detractors. Philadelphia police unions worked tirelessly to keep him on death row and since he was moved to the general prison population in 2012 they have continued to work equally tirelessly to prevent him going free.

Maureen Faulkner, the widow of Daniel Faulkner, the police officer Abu-Jamal was convicted of murdering, has been equally consistent. Earlier this year she wrote a column in the Philadelphia Inquirer in which she said the real political prisoners in this story were her family. “We committed no crime, yet we received life sentences with no possibility of parole or reprieve.”

In April, when Abu-Jamal’s case came up before a Philadelphia judge in a legal dispute over the handling of his appeals, Maureen Faulkner appeared on the steps of the court and proclaimed to local TV cameras: “Mumia Abu-Jamal will not – not ever – be free, and I will make sure of that.”

My initial letter to Abu-Jamal in August 2016 developed into a correspondence that continues two years later. Over time it mushroomed into a larger project in which I reached out to several of his peers – black radicals incarcerated like him for decades – in an attempt to understand how they came to be given such lengthy sentences and how they cope with their enduring punishment today.

Advertisement

At a time when America is still grappling with the racial legacy of slavery and segregation, when the issue of police brutality has welled up again through Black Lives Matter, when at least one in four black males born today can expect to end up in prison, and when inequality shows no sign of abating for African Americans, there is renewed interest in the perspective of the Black Panthers. Just ask Beyoncé, who injected a Black Panther homage into the 2016 Super Bowl.

Black Pantherism’ is but a synonym for Blackness itself. For in a society deeply imbued with white supremacy, Blackness is itself a crime

And so Abu-Jamal and I began to correspond. We would contact each other through a closed email network set up by the Pennsylvania prison system.

With each email I would try and probe a little deeper, trying to get under the skin of what it was to be a black radical for whom, in some sense, time had stood still through long years of incarceration. Sometimes he would answer in short staccato emails, as though his mind were elsewhere; sometimes he would be thoughtful and expansive.

Sometimes he didn’t reply for weeks. It’s remarkable how busy a man locked up around the clock can be. “I’ve been meaning to write to you,” he said in November 2017, “but my projects (I just finished my booklet last nite) have eaten my time – oops, I’m about to get on the phone…”

In our exchanges he reflected on how he had become involved as a teenage boy in the black resistance struggle of the late 1960s, and why decades later so many black militants remain behind bars. He talked also about how his militancy as a former Panther relates to the critical movements of today, notably Black Lives Matter, which controversially he called a “continuum” of the Black Panthers.

Early on, I asked him why he thought the judicial system had borne down on him singularly harshly by giving him the death penalty. He replied in an email on 23 September 2016: “I think we posed an existential challenge to the very legitimacy of the System – and it unleashed unprecedented fury from the State. That’s why they used any means, even illegal, to extinguish what they saw as a Threat.”

He added: “The State reserves its harshest treatment for those it sees as revolutionaries.”

Pinterest

Construction workers at a rally in 2001 near the Criminal Justice Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, calling for Mumia Abu-Jamal’s execution. Photograph: Tom Mihalek/AFP/Getty Images

Mumia Abu-Jamal was born Wesley Cook and brought up in a low-income African American neighborhood of Philadelphia. He was given the name Mumia by a high school teacher as part of a class on African culture and he later changed his last name to Abu-Jamal (“father of Jamal”) when his son was born in 1971.

In 1968, when he was 14, a friend introduced him to a copy of the Black Panther party’s newspaper, and he was instantly transfixed. “A sister gave me a copy of The Black Panther newspaper and I was dazzled,” he wrote to me in an email. “I made up my mind to become one of them.”

Three years of head-spinning activity ensued as a Black Panther in Philadelphia. The party, though relatively small in numbers, quickly began to make an impact with its revolutionary talk, its audacious opposition to police brutality in black neighborhoods, and its social programs that quickly expanded to include food and clothing banks for low-income communities and even Black Panther elementary schools.

Advertisement

The city at that time, he told me, was a place of “intoxicating freedom, and gripping fear. The freedom? To be active in a part of a vast Black Freedom Movement was Living, Breathing, Being Freedom. We spoke and acted in the world in ways our parents never dreamed possible.”

The fear? “Every Panther knew, in her/his heart, that the State was willing to kill a Panther in his/her bed.”

He was alluding to the death of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton in a police raid on a Panther house in Chicago in December 1969. Hampton was shot and killed while asleep in bed. A subsequent federal investigation into the killing found that in the shoot-out the Panthers had fired one bullet, while the police fired up to 99.

“I was one of several Panthers sent to Chicago,” Abu-Jamal wrote in an email. “We entered the apartment. We saw the bullet holes which raked the walls. We saw the mattress, swollen with Fred’s blood. I was 15.”

The death of Hampton was just one of several bloody shootouts that erupted as confrontations between law enforcement and the Panthers became more frequent. Many years later it was revealed that the FBI had put several prominent members of the movement – the teenage Abu-Jamal included – under a vast web of surveillance.

The State reserves its harshest treatment for those it sees as revolutionaries

The FBI’s director J Edgar Hoover had come to see the Panthers, with their links to revolutionary parties around the world and growing popularity in black inner cities, as a major threat to national security. He instructed his agents to redirect the secret domestic surveillance operation, known as “Cointelpro”, specifically onto black radicals.

Advertisement

Abu-Jamal recalled the naivety that existed within the Panther party about the governmental forces targeted at them.

“We didn’t know about Cointelpro. When people raised questions, we’d laugh at them and tell them: ‘Stop being paranoid!’ The very idea the government would read your mail, or listen to your phone calls, was crazy! We never believed we were important enough.”

The FBI certainly did think them important enough. It made sure the party was thoroughly infiltrated with informers, leaders were rounded up and imprisoned, internal dissent fomented. By 1970 open warfare had started to break out between west coast and east coast factions of the party, leading to threats, expulsions and internecine violence.

An exodus of Panthers began, among them Abu-Jamal who quit the party towards the end of 1970. From then, he turned his hand to journalism, becoming a prominent reporter on Philadelphia race relations as well as a vocal supporter of Move.

It was not until 1982 that the Black Panther party formally disbanded. By then Abu-Jamal was already in captivity and facing murder charges relating to the death of Officer Faulkner.

The events of the early hours of 9 December 1981 have been the subject of reams of analysis and conjecture over the past almost four decades. Faulkner carried out a traffic stop at an intersection in Philadelphia, pulling over William Cook, Abu-Jamal’s younger brother.

Pinterest

Demonstrators supporting Mumia Abu-Jamal in Los Angeles, California, in 2000. Photograph: Roberto Schmidt/AFP/Getty Images

Abu-Jamal at that time was working as a taxi driver to supplement his journalism income. He happened to be driving past when he spotted the altercation between Faulkner and his brother.

Advertisement

A shootout occurred. Faulkner died at the scene from gunshot wounds. Abu-Jamal was shot once in the stomach. In June 1982 he was put on trial, found guilty and sentenced to death.

Since then he has consistently professed his innocence of the charges leveled against him, though he has declined to discuss what actually did happen that night. I wrote to Abu-Jamal in June asking him whether he’d talk to me about Faulkner’s death. I said: “So what did happen? What do you recollect of the incident? Who shot Officer Faulkner?”

Earlier this month he replied to me. He began the email by saying that he’d just returned from the eye doctor who in order to inspect his inner eye had dilated his pupils. “My vision is so impaired that I can’t read the newspaper so this won’t be long, I haffa be quite brief.”

He did address his case, in general terms. “The question arises, how can you getta fair result with an unjust, unfair process? Due process. A judge who wuzza life member of the FOP [Fraternal Order of Police] said at one of my hearings: ‘Justice is just an emotional feeling’.”

Abu-Jamal did not address in the email my questions about the specifics of his own case.

While doubts persist about the nature of the crime, what is not in doubt is that Abu-Jamal’s prosecution, as he remarked, was riddled with flaws. Amnesty International investigated it in 2000 and concluded that though they could not pronounce on his guilt or innocence, “numerous aspects of this case clearly failed to meet minimum international standards”.

A long struggle to fend off execution followed, sending reverberations around the globe. Twice he had a death warrant issued that would have sent him to the death chamber; twice it was averted in the courts.

Every Panther knew, in her/his heart, that the State was willing to kill a Panther in his/her bed

It took two decades of almost constant appeals to overturn his death sentence in a federal court. Since moving off death row, he has more privileges but he’s less in the limelight now, less of an international figure, as he alluded to when I asked him how much mail he receives. “I probably get 6-10 pieces a day or 30 to 50 pieces a week (which is nothing like I used to get).”

He has slowed down in recent years in other ways too. “I used to read 2-3 books a week. Now? 2 per month. It’s a different environment. I leave the cell often here: not so on death row.”

As he gets older, health becomes more of an issue. He fought a tough legal battle after the Pennsylvania department of corrections denied him treatment for Hepatitis C, winning a federal court ruling that has set a precedent that will help thousands of other prisoners across the country defeat the virus.

Advertisement

He complains though that the prison authorities are still denying treatment to many inmates on grounds they aren’t sick enough. “People are dying from their denials and delays. Literally. $$$ over life.”

Despite health issues, he keeps closely engaged with political currents. In March I asked him what he thought were the similarities and contrasts between the Black Panthers in the 1970s and Black Lives Matter today. I was curious to see whether he was critical of BLM in an echo of the criticism the Panthers directed in the 1970s at the civil rights movement – that it’s a reformist compromise rather than the black power revolution that’s needed.

He replied that in his view the Panthers and BLM are “part of a continuum. The BPP was born in an age of global revolution. Black Lives Matter came into being during an era of sociopolitical conservatism, and rightist ideological ascendance. What is possible is subject to the zeitgeist of the period.”

He went on: “I am reminded of [Frantz] Fanon’s adage: ‘Every generation must, out of relative obscurity, find its destiny, and fulfill it or betray it.’ I think both movements have done so, if only in their own ways.”

He also keenly follows his fellow imprisoned black radicals’ efforts to gain their freedom, decades after they were arrested. In one email, sent in May, he commented on the release of Herman Bell, a former Black Panther and member of its clandestine wing the Black Liberation Army, who had secured his own parole a couple of months before partly by denouncing his involvement in the struggle. There was “nothing political” in the double police killing that he was involved in, Bell told the parole board, “it was murder and horribly wrong”.

Abu-Jamal told me that in his view Bell’s release was the exception that proves the rule. “If a man is only truly parole-eligible if he renounces his political ideas, how could those who aren’t ‘eligible’ because they aren’t renunciators be seen as anything but political prisoners?”

What I always find interesting is how profoundly different the American systems of ‘justice’ are from those that exist abroad

There are many who will disagree with the argument that the 19 imprisoned Black Panthers and Move members are political prisoners. For the police unions and the families of victims, they are “cop killers”, pure and simple.

Yet no one could accuse Abu-Jamal of being a “renunciator”. Since coming off death row he has been resentenced and put onto life without parole. That means that he has no chance of ever persuading a parole board to release him, which in turn, paradoxically, has given him his own kind of freedom – to speak his mind.

“Parole is a political tool,” he wrote. “It’s especially used against radicals to punish them for their political beliefs. I think it should be abolished. Period.”

One of the most evocative emails he sent me was composed on New Year’s Eve last year. Maybe the end of the year had put him in a reflective mood, or maybe the calendar means nothing to a man who has lived for 37 years in a cell.

In any case, he started riffing again, this time about the US justice system. He talked about how parole appeared to be a pipe-dream for black radicals in particular.

He referenced the Move 9 again, the group from his home town of Philadelphia, six of whom will next week mark the 40th anniversary of their incarceration. He spoke too of other former Black Panthers who had in recent years been granted release orders only to have them overturned by the higher courts.

Then he switched, in his own rather professorial way, to a more personal point. “What I always find interesting is how profoundly different the American systems of ‘justice’ are from those that exist abroad,” he wrote. “Under Pennsylvania law, life means life, with no parole eligibility for anybody.”

For “anybody”, read Mumia Abu-Jamal. He went on to spell out for my benefit his probable fate.

Legal scholars and activists in Pennsylvania have a name for it, he said: “Death by incarceration”.

Black power behind bars

Over two years, Ed Pilkington has interviewed eight of the 20 African American radicals languishing in prison for their actions during the 1970s black liberation struggle.

Born in a cell: the extraordinary tale of the black liberation orphan

Published:

31 Jul 2018

Born in a cell: the extraordinary tale of the black liberation orphan

A siege. A bomb. 48 dogs. And the black commune that would not surrender

Published:

31 Jul 2018

A siege. A bomb. 48 dogs. And the black commune that would not surrender

America's black radicals – a timeline in pictures

Published:

30 Jul 2018

America's black radicals – a timeline in pictures

The Black Panthers still in prison: after 46 years, will they ever be set free?

Published:

30 Jul 2018

The Black Panthers still in prison: after 46 years, will they ever be set free?

promoted links

from around the web

Recommended by Outbrain

About this Content

Skip to main content

The Guardian - Back to home

Black power behind bars

Born in a cell: the extraordinary tale of the black liberation orphan

Debbie Africa, one of the radicals who was released a week ago after 40 years, and her son, Mike Africa. Photograph: Mark Makela for the Guardian

Mike Africa Jr has spent 40 years of his life with both parents behind bars. Then one day in June, his life changed. Ed Pilkington tells his story

Tue 31 Jul 2018 09.00 BST

Shares

1,618

The placenta was the trickiest part. How to dispose of it without it making a mess that would alert the guards that a child had just been born in a prison cell?

There was no medical equipment, no painkillers, no sterilized wipes or hygienic materials of any sort. When it came to cutting the umbilical cord in the absence of scissors, well, that was the easy part: just use your teeth.

But Debbie Sims Africa was more stressed about the placenta. It was 1978, she was 22 years old and five weeks into what would turn out to be a 40-year prison sentence.

'This is huge': black liberationist speaks out after her 40 years in prison

Read more

She was determined to give birth on her own without any involvement of the jail officers so she could spend some precious time with the baby. In the end, a co-defendant helped her out, scooping up the placenta in her hands and secreting it to the shower room where she flushed it down the prison toilet.

The plan worked. Debbie Africa got to spend three wonderful days with her baby son. She hid him under a sheet and when he cried, other jailed women would stand outside the cell and sing or cough to obscure the noise.

She knew it couldn’t last, as jail rules prohibited mothers being with their children. At the end of the three days she informed the jailers of the baby’s existence and, once they had got over their astonishment, they arranged for the mother and son to be separated and for the child to be taken to the outside world.

So begins the extraordinary life of Mike Africa Jr, a man born in a prison cell, and his incarcerated parents. As he approaches his 40th birthday in September, he reflects on what a crazy ride it’s been.

Mike Davis Africa Jr. Photograph: Ed Pilkington for the Guardian

Advertisement

He was born to a mother accused and later convicted of third-degree murder in one of the most dramatic confrontations with law enforcement of the 1970s black liberation struggle. Not only was Debbie Africa sentenced to 30 years to life for the death of a police officer, so too was her husband, Mike Africa Sr, father to Mike Jr, who was caught up in the same confrontation and given the same punishment.

Which makes Mike Jr a penal orphan of the black power movement. For almost 40 years, he visited both his parents in separate penitentiaries but never saw either of them outside prison walls. Last month Debbie was finally released from prison on parole, but his father remains in captivity and to this day he has never seen the two of them together.

Debbie and Mike Sr, both now 62, are two of the Move Nine, the group of black radicals who were collectively held responsible for the death of Officer James Ramp during a massive police shoot-out at their communal home in Powelton Village, Philadelphia on 8 August 1978. The group, whose members take “Africa” as their last name as a political badge, were resisting eviction.

They were like the Black Panthers crossed with nature-loving hippies. Black power meets flower power

Move was one of the more extraordinary elements of the 1970s black liberation struggle. Deeply committed to fighting police brutality in African American communities, they were also devoted to caring for animals and the environment.

The Resistance Now: Sign up for weekly news updates about the movement

Read more

They were like the Black Panthers crossed with nature-loving hippies. Black power meets flower power.

They lived in a communal house along with dozens of stray dogs and cats where they would preach their political beliefs day and night at high volume through bullhorns, driving their neighbors to despair. Over time they came to be seen as dangerous non-conformists by the Philadelphia police and city government, leading to a drawn-out confrontation that culminated in the 1978 siege and gunfight involving hundreds of police that saw the death of Officer Ramp and sent nine of the black radicals to prison, potentially for life.

The Move Nine were accused of firing the first shot and of killing Ramp. Yet they have always claimed innocence. They deny that they shot at anybody and blame the officer’s death on accidental “friendly fire” from other armed police.

Ramp, 52, was a former marine who had served with the Philadelphia police department for 23 years. He was killed by a single bullet. Yet all nine Move members were convicted of his murder.

Move members in front of their house in the Powelton Village section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Photograph: Leif Skoogfors/Corbis via Getty Images

I met Debbie Africa and her son as part of research into incarcerated black radicals that began more than two years ago. The starting point was the Angola Three, former Black Panthers who had endured unprecedented stretches in solitary confinement in Louisiana’s notorious Angola prison.

That began a journey that would bring me to interview several members of the Move Nine as well as former Black Panthers and members of the Black Liberation Army who remain incarcerated in some cases half a century after their arrests. It would culminate with a day spent with Debbie and Mike Jr, mother and son, as they celebrated their first time together beyond prison walls.

Debbie Africa was eight months pregnant during the 1978 siege. During the shoot-out she was holed out in the basement of the Move house, where she was bombarded by water cannons and tear gas and had to fumble her way out in the dark carrying her first child, her two-year-old daughter Michelle.

No evidence was presented at trial that she pulled the trigger or ever touched a gun. But she was convicted nonetheless as a murderer and conspirator.

Mike Sr remains behind bars in Graterford correctional institution in Pennsylvania. But last June, Debbie Africa became one of very few black liberationists convicted of violent acts from the 1970s to be released on parole having convinced the board she was no threat to society.

D

ebbie and Mike Jr talked to me at his home in a small town outside Philadelphia just two weeks after she had been released on parole from Cambridge Springs prison. They were both still clearly awestruck to be in each other’s company after so long – Mike’s sporadic prison visits to both his parents were nothing like this.

It’s the little things that have dumbfounded Mike Jr most. The first morning after they got back to his house, they were sitting at breakfast wearing no shoes.

“It was the first time I’ve ever seen her feet, and it was the first time she’d ever seen my feet since I was three days old in her cell,” he said.

Pinterest

Debbie Africa and her son, Mike Africa, in Clifton Heights, Pennsylvania. Photograph: Mark Makela for the Guardian

Debbie Africa described waves of overpowering emotion. “I can’t believe this is happening,” she said. “I’ll just start hugging him in the supermarket and people will be giving us strange looks.”

She talked about the wrench of letting her son go when he was three days old. “It was a hard, hard decision. I wanted what was best for him and I knew that was not to get close to me at any level. So I had to break the bond.”

Mike Jr was raised during his childhood by his grandmother and by a succession of different female members of the Move organization as part of its communal ethic. “I was a community kid, I had many mothers,” Mike Jr said in a deadpan voice, as though describing the weather.

Every Mother’s Day he makes the rounds of his “mothers”. He drives around bearing cards and flowers which he drops off at the homes of at least six women. He rattled off their names: Bert, Sue, Romana, Pam, Mary, Teresa.

Now he’ll be able to put flowers in the hands of his true birth mother. He had no idea who she was, nor who his father was, until he was about six or seven when their relationship to him was made clear to him.

“I didn’t know she was in prison, I didn’t know any of it. I thought that the person caring for me was my mother.”

He looks back on his childhood and recognizes that some aspects of his upbringing were less than ideal. “Who teaches a kid how to brush his teeth or take a bath but his parents. I didn’t know how to wash my hair ’til I was 15.”

Through his childhood he was taken to visit both parents in separate prisons, maybe once or twice a year. But for years he had no idea why they were locked up. When friends at school asked about him about them, he would demur or make up stories because he was embarrassed to reveal his ignorance.

I feel relief. Big relief. I never knew she would come out alive

Mike Africa Jr

It was only when he was 14 and sitting with his father in Graterford that the penny dropped. He asked Mike Sr whether there was anybody held in the prison who had done something really bad, like killing somebody.

“Yeah,” Mike Sr replied, “me”.

“He didn’t go on to explain,” Mike Jr recalled. “I was frightened. Was he going to be in here forever? I was crying my eyes out trying to figure it out, but I couldn’t explain to him why I was crying. I couldn’t put it into words.”

Mikr Jr said it took him years to put the pieces together. “I was left to figure it out for myself, to fend for myself.”

But neither son nor mother are ones to dwell on the wounds of the past. I asked Debbie Africa whether she regretted that by her actions as a black liberationist and Move member she had put her son through so much pain.

“There are always going to be things in my life that I wish didn’t happen,” she said. “I do truly wish that what happened to my son hadn’t happened, I do truly. But I look at the man he is now, and I love it.”

Pinterest

Father and son, Mike Davis Africa Sr and Jr, in Huntingdon state correctional institution in 1993. Mike was 14. Photograph: Courtesy of Mike Davis Africa Jr

Having spent two days in the company of Mike Africa Jr outside Philadelphia, I can see what she means. He has turned out remarkably poised for someone with his chaotic childhood résumé.

He runs his own small business as a landscape gardener, is married and has four children of his own. He is a proud member of Move, has never owned or even held a gun, and his house is comfortable and full of light, though it was notable how much neater it was the second time I visited following Debbie’s release. At last she has begun fulfilling that ritual of parents everywhere: tidying up after their child’s mess.

On Mike Jr’s part he’s similarly delighted his mother has turned out as well-balanced, sociable and positive as she is, given 40 years in correctional institutions. “I feel relief. Big relief. I never knew she would come out alive. When people come out of prison they can be sick in the head, but this transition of her coming to my house has been the smoothest major transformation of my life.”

Now the challenge is to help Mike Africa Sr secure parole, and so complete the family. His next appearance before the parole board is in September, and they are all already on tenterhooks.

A paradox of Debbie Africa’s release is that under her parole terms she is not able to communicate in any form with her husband because he is classified as a co-defendant and thus is out of bounds. The last time they saw each other in the flesh was in 1986. Since then they had been allowed to write to each other from their cells, and in that way managed to keep their bond alive.

I can’t believe this is happening. I’ll start hugging him in the supermarket and people will be giving us strange looks

Debbie Sims Africa

Now that the letter-writing has been stopped all they have in terms of connection is Mike Jr acting as a go-between. He lets each parent know how the other is doing. He also acted as my go-between, putting questions to his father which Mike Sr answered in a phone call to him.

How confident is Mike Sr, I asked, as he heads into the parole hearing?

“I’m confident that I’m going to tell the truth. I’m confident that I deserve parole. I’m confident I would never be considered a danger to the community ever again. We never intended for anyone to get hurt, and regret that anyone did get hurt.”

Then he added: “What I’m not confident about is what they’re going to do, I have no control over that.”

He said the knowledge that his wife was now at home with his son and daughter was a great comfort to him. But it also heightened his desire to be with them all.

“Forty years of wanting, anticipating. It’s like Double Dutch. You’re always on the edge of that jump rope, hopping up and down, waiting to get in, waiting for your turn.”

Topics

Black power