Democracy and Parliamentarism - Anton Pannekoek

Excerpt from a1919 text by council communist Anton Pannekoek on social democracy and communism.

Posted as a contribution to the current debate over electoralism.

Full text: https://marx.libcom.org/library/social-democracy-communism-anton-pannekoek

4. Democracy and Parliamentarism

Social democratic doctrine never concerned itself with the problem of discovering the political forms its power would assume after having reached its goal. The beginning of the proletarian revolution has provided the practical answer to this question, thanks to the events themselves. This practice of the first stages of the revolution has enormously increased our ability to understand the essence and the future path of the revolution; it has enormously clarified our intuitions and contributed new perspectives on a matter which was previously vaguely outlined in a distant haze. These new intuitions constitute the most important difference between social democracy and communism. If communism, in the points discussed above, signifies faithfulness to and the correct extension of the best social democratic theories, now, thanks to its new perspectives, it rises above the old theories of socialism. In this theory of communism, Marxism undergoes an important extension and enrichment.

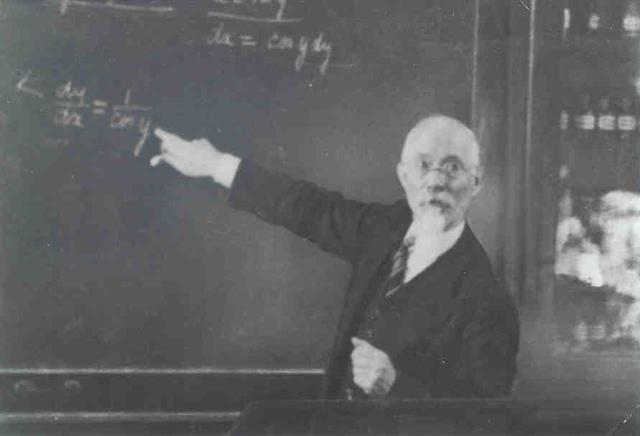

Up until now, only a few people were aware of the fact that radical social democracy had become so profoundly estranged from Marx’s views in its concept of the State and revolution—which, furthermore, no one had even taken the trouble to discuss. Among the few exceptions, Lenin stands out. Only the victory of the Bolsheviks in 1917, and their dissolution of the National Assembly shortly afterwards, showed the socialists of Western Europe that a new principle was making its debut in Russia. And in Lenin’s book, The State and Revolution, which was written in the summer of 1917—although it only became available in Western Europe in the following year—one finds the foundations of the socialist theory of the State considered in the light of Marx’s views.

The opposition between social democracy and the socialism we are now considering is often expressed in the slogan, “Democracy or Dictatorship”. But the communists also consider their system to be a form of democracy. When the social democrats speak of democracy, they are referring to democracy as it is applied in parliamentarism; the communists oppose parliamentary or bourgeois democracy. What do they mean by these terms?

Democracy means popular government, people’s self-government. The popular masses themselves must administer their own affairs and determine them. Is this actually the case? The whole world knows the answer is no. The State apparatus rules and regulates everything; it governs the people, who are its subjects. In reality, the State apparatus is composed of the mass of officials and military personnel. Of course, in relation to all matters which affect the entire community, officials are necessary for carrying out administrative functions; but in our State, the servants of the people have become their masters. Social democracy is of the opinion that parliamentary democracy, due to the fact that it is the form of democracy where the people elect their government, is in a position—if the right people are elected—to make popular self-government a reality.

What really happens is clearly demonstrated by the experience of the new German republic. There can be no doubt that the masses of workers do not want to see the return of a triumphant capitalism. Even so, while in the elections there was no limitation of democracy, there was no military terrorism, and all the institutions of the reaction were powerless, despite all this the result was the reestablishment of the old oppression and exploitation, the preservation of capitalism. The communists had already warned of this and foresaw that, by way of parliamentary democracy, the liberation of the workers from their exploitation by capital would not be possible.

The popular masses express their power in elections. On election day, the masses are sovereign; they can impose their will by electing their representatives. On this one day, they are the masters. But woe to them if they do not choose the right representatives! During the entire term after the election, they are powerless. Once elected, the deputies and parliamentarians can decide everything. This democracy is not a government of the people themselves, but a government of parliamentarians, who are almost totally independent of the masses. To make them more responsive to a greater extent one could make proposals, such as, for example, holding new elections every year, or, even more radical, the right of recall (compulsory new elections at the request of a certain number of the eligible voters); naturally, however, no one is making such proposals. Of course, the parliamentarians cannot do just as they please, since four years later they will have to run for office again. But during that time they manipulate the masses, accustoming them to such general formulas and such demagogic phrases, in such a way that the masses are rendered absolutely incapable of exercising any kind of critical judgment. Do the voters, on election day, really choose appropriate representatives, who will carry out in their name the mandates for which they were elected? No; they only choose from among various persons previously selected by the political parties who have been made familiar to them in the party newspapers.

But let us assume that a large number of people are elected by the masses as the representatives of their true intentions and are sent to parliament. They meet there, but soon realize that the parliament does not govern; it only has the mission of passing the laws, but does not implement them. In the bourgeois State there is a separation of powers between making and executing the laws. The parliament possesses only the first power, while it is the second power which is really determinate; the real power, that of implementing the laws, is in the hands of the bureaucracy and the departments of the State, at whose summit is the government executive as the highest authority. This means that, in the democratic countries, the government personnel, the ministers, are designated by the parliamentary majority. In reality, however, they are not elected, they are nominated, behind closed doors with a lot of skullduggery and wheeling and dealing, by the leaders of the parties with a parliamentary majority. Even if there were to be an aspect of popular will manifested in the parliament, this would still not hold true in the government.

In the personnel staffing the government offices, the popular will is to be found only—and there, in a weakened form mixed with other influences—alongside bureaucratism, which directly rules and dominates the people. But even the ministers are almost powerless against the organizations of the bureaucracy, who are nominally subordinate to them. The bureaucracy pulls all the strings and does all the work, not the ministers. It is the bureaucrats who remain in office and are still there when the next batch of elected politicians arrives in office. They rely on the ministers to defend them in parliament and to authorize funding for them, but if the ministers cross them, they will make life impossible for them.

This is the whole meaning of the social democratic concept of the workers being able to take power and overthrow capitalism by means of the normal rule of general suffrage. Do they really think they can make anyone believe that all of these functionaries, office workers, department administrators, confidential advisors, judges and officials high and low, will be capable of carrying out any sort of change on behalf of the freedom of the proletariat at the behest of the likes of Ebert and Scheidemann, or Dittmann and Ledebour? The bureaucracy, at the highest levels, belongs to the same class as the exploiters of the workers, and in its middle layers as well as in its lowest ranks its members all enjoy a secure and privileged position compared to the rest of the population. This is why they feel solidarity with the ruling layers which belong to the bourgeoisie, and are linked to them by a thousand invisible ties of education, family relationships and personal connections.

Perhaps the social democratic leaders have come to believe that, by taking the place of the previous government ministers, they could pave the way to socialism by passing new laws. In reality, however, nothing has changed in the State apparatus and the system of power as a result of this change of government personnel. And the fact that these gentlemen do not want to admit that this is indeed the case is proven by the fact that their only concern has been to occupy the government posts, believing that, with this change of personnel, the revolution is over. This is made equally clear by the fact that the modern organizations created by the proletariat have, under their leadership, a statist character and smell about them, like the State but on a smaller scale: the former servants, now officials, have promoted themselves to masters; they have created a dense bureaucracy, with its own interests, which displays—in an even more accentuated form—the character of the bourgeois parliaments at the commanding heights of their respective parties and groups, which only express the impotence of the masses of their memberships.

Are we therefore saying that the use of parliament and the struggle for democracy is a false tactic of social democracy? We all know that, under the rule of a powerful and still unchallenged capitalism, the parliamentary struggle can be a means of arousing and awakening class consciousness, and has indeed done so, and even Liebknecht used it that way during the war. But it is for that very reason that the specific character of democratic parliamentarism cannot be ignored. It has calmed the combative spirit of the masses, it has inculcated them with the false belief that they were in control of the situation and squelched any thoughts of rebellion which may have arisen among them. It performed invaluable services for capitalism, allowing it to develop peacefully and without turmoil. Naturally, capitalism had to adopt the especially harmful formula of deceit and demagogy in the parliamentary struggle, in order to fulfill its aim of driving the population to insanity. And now the parliamentary democracy is performing a yet greater service for capitalism, as it is enrolling the workers organizations in the effort to save capitalism.

Capitalism has been quite considerably weakened, materially and morally, during the world war, and will only be able to survive if the workers themselves once again help it to get back on its feet. The social democratic labor leaders are elected as government ministers, because only the authority inherited from their party and the mirage of the promise of socialism could keep the workers pacified, until the old State order could be sufficiently reinforced. This is the role and the purpose of democracy, of parliamentary democracy, in this period in which it is not a question of the advent of socialism, but of its prevention. Democracy cannot free the workers, it can only plunge them deeper into slavery, diverting their attention from the genuine path to freedom; it does not facilitate but blocks the revolution, reinforcing the bourgeoisie’s capacity for resistance and making the struggle for socialism a more difficult, costly and time-consuming task for the proletariat.