|

|  |

A reflection on freedom and conformism - Merijn Oudenampsen

flexmens.org - 02.05.2011 12:39

Here a short reflection on freedom and conformism, written for 'Mokum, a guide to Amsterdam', published in the framework of the 5th of May celebrations.

http://www.flexmens.org/drupal/?q=Amsterdam_True_Freedom_and_Repressive_Tolerance http://www.flexmens.org/drupal/?q=Amsterdam_True_Freedom_and_Repressive_Tolerance

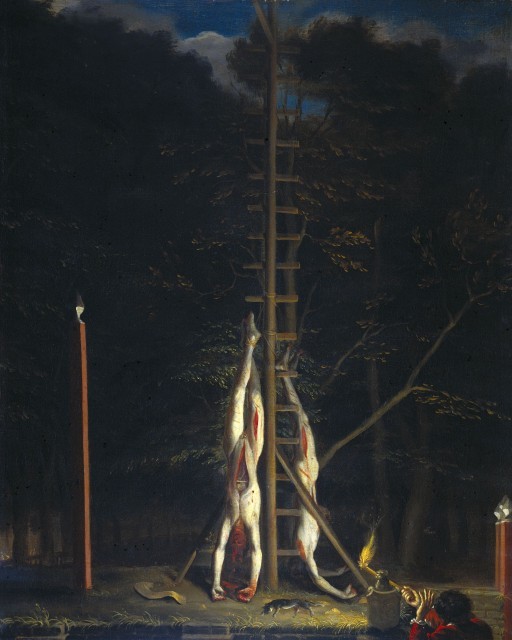

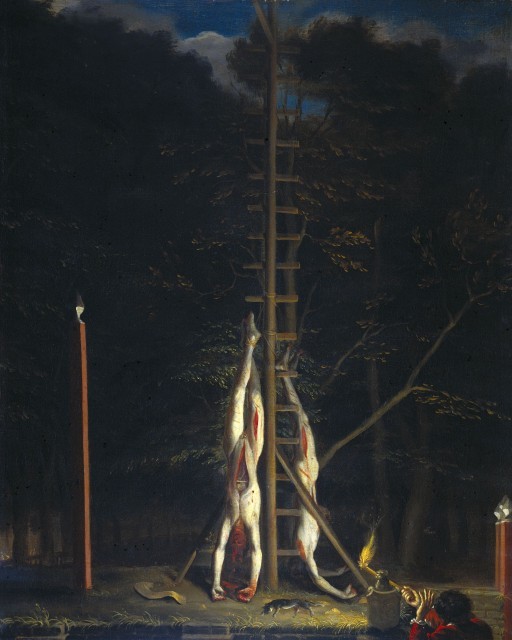

Jan de Baen- De lijken van de gebroeders de Witt (~1672-1702)

True Freedom and Repressive Tolerance

Merijn Oudenampsen

The notion of freedom is intimately bound up with the historical identity of Amsterdam, a city that takes prides in its image as a sanctuary of cultural and political expression. It remains one of the few places where the contemporary political climate of cultural and religious intolerance has not managed to gain ground. A city in which the �soft� approach to social conflict resolution still prevails long after it was declared void in the national arena. Yet at the same time Amsterdam has lost most of the spirit of freedom and rebellion it harboured as a magisch centrum in the sixties, as an Orange-Free State in the seventies and as a squatter bulwark in the eighties. Free spaces in the city are being assimilated and squatters evicted. Inflated real estate prices, combined with an extensive web of regulation enforced by overzealous inspectors, make bottom up initiatives close to impossible and structurally impair the city�s cultural life. But more importantly, the city�s population, in terms of its outlook and aspirations, seems to be in a more domesticated state than it has been in a long time. In this article I argue that the notions of �true freedom� and �tolerance� handed down to us from centuries past are at the basis of this contradictory mixture of freedom and conformism that holds sway in the city today.

Two models of power, two forms of freedom

In 1654 Grand Pensionary (leading statesman) Johan de Witt held a five-hour lecture before the Dutch States General (the governing body of the Netherlands) during which he read a text that became known as 'the deduction'. Though little known among the general public today, it is a founding document of the Dutch political system and one of the most explicit expressions of the defence of political liberties of its time. Johan de Witt proclaimed his politics of 'True Freedom', which aimed to exclude the monarchy from power, until that time broadly seen in Europe as a sacred and God given institution. Instead of the centralized power of the absolutist monarch, Johan de Witt proposed a decentralized structure of assemblies of regents:

�Freedom is better protected by the great number of good regents who have been ordered by the privileges of the land to administer it, than one person brought in from outside this group and against whom the regents always have to be on guard in order to protect freedom.�

Johan de Witt�s notion of True Freedom was inherently linked to the idea of tolerance, in those times understood as religious toleration. Baruch Spinoza, a close friend of Johan de Witt, worked this out in his Tractatus Politicus Theologicus of 1670, broadening idea of tolerance toward a secular notion of freedom of speech. Spinoza lauded the city of Amsterdam as the beneficial example of his political philosophy:

�In order to prove that from such freedom no inconvenience arises�and that men's actions can easily be kept in bounds, though their opinions be at open variance, it will be well to cite an example. Such an one is not very far to seek. The city of Amsterdam reaps the fruit of this freedom in its own great prosperity and in the admiration of all other people. For in this most flourishing state, and most splendid city, men of every nation and religion live together in the greatest harmony, and ask no questions before trusting their goods to a fellow-citizen, save whether he be rich or poor, and whether he generally acts honestly, or the reverse. His religion and sect is considered of no importance: for it has no effect before the judges in gaining or losing a cause, and there is no sect so despised that its followers, provided that they harm no one, pay every man his due, and live uprightly, are deprived of the protection of the magisterial authority.�

Two years after Spinoza wrote these words, in what has become known as the rampjaar (disaster year) of 1672, Johan de Witt and his brother were brutally lynched by a monarchist mob, their bodies mutilated and partly eaten. For some years after, the hearts of the brothers were publicly exhibited by one of the mob ringleaders. William III of Orange, who bestowed upon the monarchist mob all sorts of rewards, consequently took over power and centralized much of the decision making around his person.

This is maybe one of the most dramatic examples of the sometimes bitter conflict between two forms of power out of which Dutch political culture has developed. On the one hand there is the regent oligarchy whose notion of �True Freedom� implied the practice of power sharing and consensus that is known today as the polder model. The connected idea of religious toleration is the historical basis of what is now considered the 'soft multicultural' approach to integration. Amsterdam epitomised this form of power and freedom. On the other hand there is the notion of freedom tied to the monarchical figure of the Stadtholder, the centralized power of a military ruler with popular appeal. The Stadtholder was allied to the Calvinist church which sought to end religious toleration and forcibly assimilate the entire population into the Calvinist community. In these two models of power (the Spinozean versus the Hobbesian notion of power, if you will) we can recognize the shapes of the present contention between liberal multiculturalism and the populist right wing politics of cultural assimilation. It also makes clear that Amsterdam's soft approach to integration, though currently dithering has deep historical origins in the city's identity.

The Limits of �True Freedom� in Amsterdam: Repressive Tolerance

The tradition of True Freedom has its own particular power dynamic and, paradoxically in some ways, depends on a higher degree of conformity than the centralized model of power it fought against. Whereas the strategy of centralized power to political opposition is intolerance, the marginalization and eviction of opposition from the public sphere, the consensus model drives on tolerance: the inclusion and recuperation of subversive and oppositional tendencies. Representatives of the opposition are invited to the negotiation table where, in exchange for political leverage and structural subsidies, they are asked to adopt a role of responsibility vis � vis power. The representatives are invited to sit in the driver�s seat and to think with, not against power. In the Netherlands this has led to the widespread institutionalisation of opposition movements and underground culture from the environmental and the squatting movements to the coffeeshops, cultural breeding grounds and publicly subsidised concert halls.

Herbert Marcuse described this practice as 'repressive tolerance': �it is the people who tolerate the government, which in turn tolerates opposition within the framework established by the constituted authorities.� Marcuse built his argument on the example of the art world, citing Baudelaire on the 'destructive tolerance' of the art market, a 'friendly abyss' in which the radical impact of art, the protest of art against the established reality is swallowed up and turned into hard cash.

Under a centralized and intolerant power the rule system which is in place is so inflexible and unworkable that the general population often transgresses these rules in their daily life practices. As a consequence people do not lend much credence to the rules as such, only to the power behind it. Under the consensus model the rule system is continuously renegotiated, making for a better fit and creating a situation in which rules as such are less questioned. An example of this dynamic is the toleration of soft drugs in the Netherlands; the main argument for toleration has always been that it makes it easier for the government to control drug use. In general, when it comes to the liberties Amsterdam is famous for we find there is always a trade off involved. The practice of squatting, to take another famous example, was tolerated until the introduction of the new and still ineffective ban on squatting in 2010. The paradoxical result was that squatters fought their struggles mainly through the legal system instead of on the streets and professed as much if not more faith in the legal order than the average citizen. The breeding ground policy, set up by city hall in order to buy and legalize squats, sought to regulate Amsterdam�s cultural underground, demanding certain benchmarks and administrative obligations to be implemented, the very opposite of what the idea of an �underground� entails. It is now difficult to find any space in Amsterdam not tightly regulated and controlled by benchmarking practices.

Now in general a centralized power model is more repressive and regressive when it comes to political and cultural freedoms. The argument here is not that an absolutist regime is somehow preferable. This article has explored the contradictory nature of the Dutch consensual model, which tolerates political opposition and alternative culture by institutionalizing and regulating it. This is the basis for the particular Amsterdam mixture of toleration and over-regulation, of freedom and conformism. Spinoza famously stated that under an absolutist regime, the sovereign cannot command people�s minds, only their tongues. Under the present consensus model this has been turned on its head.

|

| aanvullingen | | Wel aardig stukje. | Pappie. - 04.05.2011 15:17

.......has led to ......etc......

Denk dat Merijn 10 jaar geleden ergens is blijven steken.

Hij was vast niet bij de representieve tolerantie zondag van

1 Mei in Utrecht of heden op bezoek bij hare majesteits gevangenen (Damschreeuwer + waxineglaasjegooier)?

En waarom, omdat hij wel gestudeerd heeft, op Indy.NL alleen in het Engels. Vertalen man! Dus doe dit interessante stukkie ook even in het nederlands en nog andere....?

| | repressive tolerance | Molotof - 04.05.2011 17:04

Maybe that's because some squatters don't read Dutch.

Spinoza's friend Adriaan Koerbagh annoyed Holland's clergymen too much, so he was sentenced in Amsterdam and died in prison doing forced labour.

| |

| aanvullingen | |