Howard Zinn over Chomsky

NN - 02.02.2011 00:17

English below

HOWARD ZINN OVER CHOMSKY

Vertaald uit: Howard Zinn, �Foreword� in Noam Chomsky, American Power and the New Mandarins (The New Press; New York 2002 [1969]) p. iii � ix.

In februari 2002 vloog Noam Chomsky naar Ankara om te getuigen ter verdediging van zijn Turkse uitgever, Fatih Tas, die werd vervolgd wegens het �produceren van propaganda tegen de eenheid van de Turkse staat.� De bedoelde �propaganda� was een boek, American Interventionism, waarin Chomsky de Verenigde Staten bekritiseert voor het voorzien van wapens aan de Turkse overheid, die ze gebruikte voor het plegen van gruwelijke daden tegen haar Koerdische minderheid die naar autonomie streeft.

http://chomsky.nl/over-chomsky/12-howard-zinn-over-chomsky http://chomsky.nl/over-chomsky/12-howard-zinn-over-chomsky

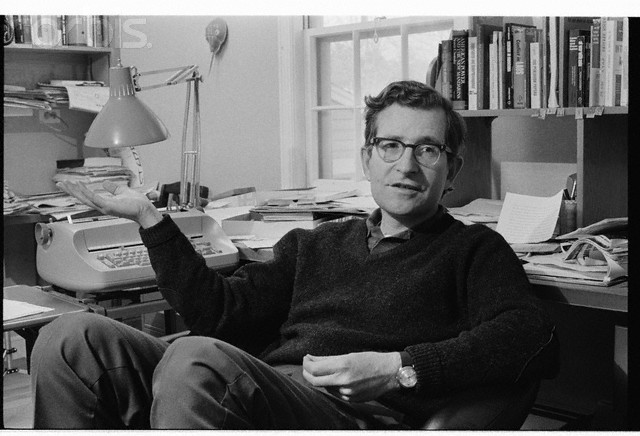

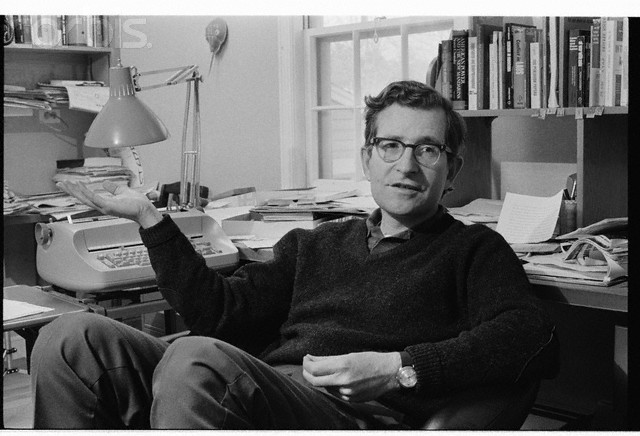

Noam Chomsky

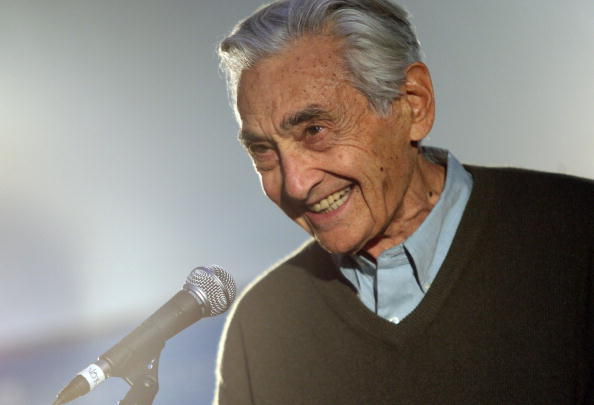

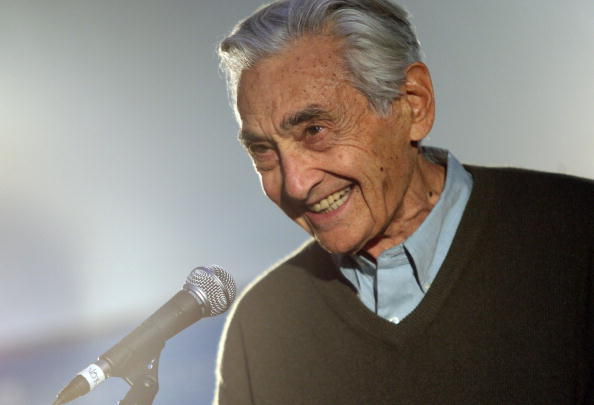

Howard Zinn

Zijn getuigenis bleek niet nodig aangezien de aanklager de aanklacht introk, zonder twijfel omdat Chomsky�s komst de rechtszaak wereldnieuws had gemaakt en de Turkse overheid haar geschiedenis van geweld tegen de Koerden niet besproken wilde zien worden voor de hele internationale pers.

Ik citeer deze gebeurtenis omdat het zo tekenend is voor Noam Chomsky om zijn diepste overtuigingen, uitgedrukt in zijn geschreven woorden, te bevestigen door zijn actieve deelname in de wereld van politieke strijd. Net voor zijn vlucht naar Turkije kwam hij terug uit Porto Alegre, Brazili�, waar 50,000 mensen vanuit vele landen bijeen waren gekomen in oppositie tegen de controle van het bedrijfsleven over de wereldeconomie. Gezamenlijk verklaarden zij: Een andere wereld is mogelijk. En vlak daarvoor was hij, met zijn vrouw Carol, naar India en Pakistan gegaan om lezingen te geven. De ene avond over lingu�stiek, de volgende avond over politiek, zoals hij zo vaak doet. Ook daar stond hij erop verder te gaan dan intellectueel discours, en nam hij met schrijfster Arundhati Roy en anderen deel aan een groeiende campagne voor economische rechtvaardigheid.

American Power and the New Mandarins werd in 1969 gepubliceerd door Pantheon Books, wiens hoofdredacteur Andr� Schiffrin heette. Schiffrin was een ongebruikelijk figuur in de uitgeverswereld aangezien de grote uitgeverij die hij leidde openstond voor radicale sociale analyse en gedurfde historische onderzoeken. Hij zag in dat, in het jaar van voortdurende escalatie van de Vietnam-oorlog , Noam Chomsky zich ontpopte als meest vooraanstaande intellectuele criticus van Amerikaans buitenlands beleid. En hij wilde dat lezers de kracht van Chomsky�s denken ervoeren.

De essays in dit boek hadden verschillende oorsprongen: een lezing aan de Universiteit van New York, artikelen in het inmiddels verdwenen radicale tijdschrift Ramparts, essays in de New York Review of Books. Wat ze allen gemeen hebben is het krachtig vasthouden aan egalitaire principes, een nietsontziende ontleding van Amerikaanse imperiale wreedheid, en een vernietigende kritiek op Amerikaanse intellectuelen, de �nieuwe mandarijnen� die dienstbaar blijven, openlijk of subtiel, aan de heersers van de maatschappij.

Geen van Noam Chomsky�s politieke geschriften is abstract, theoretisch, academisch. Ze zijn altijd doordrongen van de realiteit van sociale strijd, zijn argumenten nauwkeurig gedocumenteerd, bijna tot op het punt waarop hij zijn lezers overstelpt met informatie. Men kan hem niet lezen zonder onder de indruk te zijn van de breedte van zijn belezenheid.

Zonder twijfel de meest bekende van zijn essays in deze bundel is �De Verantwoordelijkheid van Intellectuelen,� welke in juni 1966 als lezing aan Harvard begon en in februari 1967 in de New York Review of Books verscheen. Dit was geen academische oefening. �We kunnen nauwelijks de vraag ontwijken tot op welke hoogte het Amerikaanse volk verantwoordelijk is voor de barbaarse Amerikaanse aanval op een grotendeels hulpeloze rurale bevolking in Vietnam�.�

Waarom was Chomsky, een wereldbekende taalfilosoof, wiens lingu�stische werk vaak beschreven werd als vergelijkbaar in zijn veld met dat van Einstein in de fysica en Freud in de psychologie, aan het schrijven over de oorlog in Vietnam? Omdat, zoals hij in dit essay schreef, �het de verantwoordelijkheid van intellectuelen is de waarheid te spreken en leugens te ontbloten.�

Dat essay was zonder twijfel ��n van de meest belangrijke geschriften die uit de Vietnam-oorlog voortvloeiden. Het verscheen op een moment dat de Amerikaanse aanval op Vietnam een hoogtepunt aan het bereiken was � in 1966 waren 200,000 troepen onderweg naar Vietnam en de bombardementen op Noord en Zuid-Vietnam vernietigden dorpen, ru�neerden het land, gebruik makend van de meest dodelijke wapens tot nog toe ontworpen voor luchtoorlogen. Clusterbommen met hun duizenden exploderende kogeltjes, �Daisy Cutters� die een gebied van bijna 100 meter in diameter totaal vernietigden, en zware B-52 bommenwerpers die het platteland terroriseerden.

Het Amerikaanse volk steunde de oorlog grotendeels nog, maar de pers begon te rapporteren over de vernietiging veroorzaakt door de bombardementen, en niet alleen in Noord-Vietnam, de vijand, maar ook in Zuid-Vietnam, dat de Verenigde Staten zogenaamd beschermden. Charles Mohr schreef in de New York Times dat �weinig Amerikanen beseffen wat hun land Zuid-Vietnam aandoet met luchtmacht � dit is strategisch bombarderen in een bevriend land � onschuldige burgers sterven iedere dag in Zuid-Vietnam.�

Toen Chomsky�s essay verscheen waren er al demonstraties tegen de oorlog door het hele land, maar intellectuelen waren verdeeld. Sommigen steunden de anti-oorlogsbeweging, sommigen verdedigden de oorlog, anderen waren onzeker, of, wanneer tegen de oorlog, voorzichtig met het uitspreken van hun oppositie. Door het ontrafelen van argumenten van intellectuele apologeten voor Amerikaans beleid, en het door middel van voorbeeld laten zien van wat eerlijkheid vereiste, was Chomsky�s essay een krachtige duw voor het bewustzijn en het gevoel van verantwoordelijkheid van hiervoor zwijgzame toeschouwers.

Hoe kwam Chomsky zelf dit gevoel van verantwoordelijkheid te voelen? Waarom wijdde hij, in plaats van tevreden te zijn met zijn prestigieuze reputatie op de academie, zijn geest en energie aan de oorlog die voortraasde in Vietnam, aan de bombardementen op boerendorpen, de met napalm bestookte kinderen, de ongelukkige soldaten die naar de andere kant van de wereld waren gezonden om te sterven voor een zaak die niemand rationeel kon uitleggen.

Niemand kan een persoon�s morele ontwikkeling uitleggen aan de hand van vroege ervaringen. Maar deze moeten in ogenschouw worden genomen als deel van een complexe moza�ek van oorzaken. Noam Chomsky groeide op in Philadelphia in de jaren van de Depressie, als zoon van immigranten, en herinnert zich dat hij als kleine jongen �de politie vrouwelijke stakers in elkaar zag slaan buiten een textielfabriek.�

Als tienjarige raakte hij ge�nteresseerd in de burgeroorlog in Spanje en schreef hij een editorial voor zijn schoolkrant over de val van Barcelona. Wellicht was het Barcelona�s spannende, inspirerende ervaring met anarchisme in de eerste jaren van de oorlog in Spanje die hem als dertienjarige in de boekhandels deed zoeken naar boeken over anarchisme, en daarna een levenslange sympathie voor anarchistische idee�n.

Aan de Universiteit van Pennsylvania studeerde hij lingu�stiek onder Zellig Harris, ging door naar een zeer begeerde Junior Fellowship aan Harvard, en in 1957, op negentwintig-jarige leeftijd, schreef hij zijn revolutionaire studie over taal, Syntactic Structures, waarin hij beweerde dat er een aangeboren capaciteit voor taal is in alle mensen, een �universele grammatica.�

De connectie tussen zijn baanbrekende werk in de lingu�stiek en zijn politieke overtuigingen ligt in zijn geloof dat er een �fundamentele menselijke natuur is gebaseerd op een instinct voor vrijheid.� Dit idee ligt ten grondslag aan zijn lange betrokkenheid bij bewegingen voor vrede en sociale rechtvaardigheid.

Ik ontmoette Noam Chomsky voor het eerst in 1966. Ik was recentelijk naar het Noorden verhuisd na zeven jaar lesgeven aan Spelman College in Atlanta en betrokkenheid bij de zuidelijke beweging tegen rassensegregatie. Noam en ik zaten naast elkaar op een vlucht naar Jackson, Mississippi, als deel van een delegatie vanuit New England om de massale arrestatie van zwarte mensen in Jackson te onderzoeken. Die reis was het begin van een lange vriendschap.

Hij was al begonnen met protesteren tegen de oorlog in Vietnam in 1964, het jaar waarin de grootschalige interventie van de Verenigde Staten begon. In de jaren die volgden groeide hij uit tot een onvermoeibare spreker bij bijeenkomsten en teach-ins. We deelden vele malen het sprekersplatform, en ik werd me al snel bewust van zijn ongelofelijke capaciteit voor het onthouden van informatie en het hiervan met grote kracht en eloquentie presenteren aan zijn publiek.

Maar hij was nooit tevreden met intellectueel werk alleen � met spreken en schrijven. Tijdens de grote demonstratie naar het Pentagon in 1967 werd Noam gearresteerd, samen met vele anderen. Achteraf schreef hij over dat voorval, opgenomen in deze bundel als �Over Verzet,� als een voorbeeld van de overgang �van dissidentie naar verzet,� naar burgerlijke ongehoorzaamheid, waarbij hij bleef benadrukken dat verzet tegen de wet slechts deel was van een spectrum van mogelijke reacties op onrechtvaardigheid, en dat de meer gematigde, minder dramatische vorm, dissidentie, ook noodzakelijk was.

Die keer bij de Pentagon-demonstratie belandde Noam in een cel met Norman Mailer, die, in zijn klassieke beschrijving van die gebeurtenis, The Armies of the Night, zijn celgenoot omschrijft als �een ranke, spitsige man met een ascetische uitdrukking en een uitstraling van zachte maar absolute morele autoriteit� die �zich ongemakkelijk leek te voelen bij de gedachte dat hij maandag college zou missen.�

In de lente van 1971 waren Noam en ik deel van wat mij nog steeds voorkomt als een gek klein �affinity-groepje� dat naar Washington afreisde om deel te nemen aan acties van burgerlijke ongehoorzaamheid � het blokkeren van de straten richting de bruggen over de Potomac � als een protest tegen de oorlog. Met ons waren de historica Marilyn B. Young, de voormalig overheidsexpert Daniel Ellsberg (nog niet onthuld als de distributeur van de geheime Pentagon Papers), de bioloog Mark Ptashne, en Fred Branfman, die was teruggekeerd van zijn werk in de rurale dorpen van Laos, en enkele anderen. We deden niks hero�sch, bereikten weinig, maar maakten op deze aparte wijze onze gevoelens over de oorlog duidelijk.

Noam en ik waren deel van de sprekers bij wat ik de laatste teach-in van de Vietnam-oorlog heb genoemd. Het was eind april 1975, en Amerikaanse troepen waren nu uit Vietnam. Maar de Verenigde Staten voorzag de impopulaire en corrupte regering van Zuid-Vietnam, die belaagd werd door een Noord-Vietnamees leger, nog steeds van wapens. De teach-in, op de Brandeis Universiteit, was een protest tegen de voortdurende Amerikaanse interventie. Midden in de bijeenkomst kwam een student het gangpad afgerend met in zijn hand een spoedbericht, roepende: �Saigon is gevallen. De oorlog is voorbij,� en het auditorium barstte uit in gejuich.

Na de oorlog stopte Chomsky niet met zijn meedogenloze kritiek van Amerikaanse geheime en openlijke interventies in verschillende delen van de wereld. Toen de Reagan-administratie een blokkade van de revolutionaire Sandinista-regering in Nicaragua afkondigde, bezetten we met zijn vijfhonderden het federale John F. Kennedy-gebouw in het centrum van Boston, en werden gearresteerd. Noam en ik, en alle anderen, werden aangeklaagd onder een oud statuut van Massachusetts: �Failure to quit the premises [het niet verlaten van het pand].� Die aanklacht � �failure to quit [weigeren om te stoppen]� � zou heel goed Noam en eigenlijk de hele protestbeweging in het land kunnen omschrijven.

Sinds de eerste uitgave van American Power and the New Mandarins is Noam Chomsky, door middel van zijn tientallen boeken en honderden publieke lezingen, erkend als vooraanstaande intellectuele criticus van overheidsbeleid, de meest invloedrijke woordvoerder voor de principes van vrede en rechtvaardigheid in dit land.

Slechts ��n voorbeeld van zijn pionierswerk: bijna eigenhandig bracht hij de horrordaden op Oost-Timor door de Indonesische overheid, die wapens gebruikte die geschonken werden door de Verenigde Staten, onder de aandacht van het land. De campagne duurde jaren, waarin grote groepen mensen begonnen te begrijpen was er gebeurde op dat afgelegen Pacifische land.

Uiteindelijk, na misschien 200,000 doden, met voortdurend verzet door de Oost-Timorezen, en meer en meer internationale aandacht, trok de Verenigde Staten haar steun in, stemde de Indonesische overheid toe met verkiezingen, en won Oost-Timor haar onafhankelijkheid.

In deze uitgave krijgt de lezer een proefje van Noam Chomsky�s verreikende politieke en historische interesses � de burgeroorlog in Spanje, de achtergrond voor de Pacifische oorlog met Japan. Maar in alle essays vindt men de aanhoudende aanwezigheid van de oorlog in Vietnam, waar hij zijn intellectuele krachten toe wendt op zo�n manier alsof hij tegen ons allen zegt: dit is de verantwoordelijkheid van intellectuelen, om welke gave we ook hebben te gebruiken � om leugens bloot te leggen en de waarheid te vertellen � in het belang van het cre�ren van een betere wereld.

English - Howard Zinn on Chomsky

Howard Zinn, �Foreword� in Noam Chomsky, American Power and the New Mandarins (The New Press; New York 2002 [1969]) p. iii � ix.

In February 2002, Noam Chomsky flew to Ankara, prepared to testify in defense of his Turkish publisher, Fatih Tas, who was being prosecuted for �producing propaganda against the unity of the Turkish state.� The �propaganda� in question was a book, American Interventionism, in which Chomsky criticizes the United States for supplying weapons to the Turkish government, which it used to commit atrocious acts against its Kurdish minority seeking autonomy.

It turned out that his testimony was not needed, because the prosecutor withdrew the charges, no doubt because Chomsky�s appearance had brought world attention to the trial, and the Turkish government did not want its record of violence against the Kurds brought out in the courtroom with the international press on hand.

I cite this event because it is so characteristic of Noam Chomsky to affirm his deepest beliefs, expressed in his written words, by his active participation in the world of political combat. Before his flight to Turkey he had just returned from Porto Alegre, Brazil, where 50,000 people from many countries had gathered, in opposition to corporate control of the global economy, to declare: Another world is possible. And just before that he had gone, with his wife Carol, to India and Pakistan, to lecture � as he often does � on linguistics one evening, on politics the next. There too, he insisted on going beyond intellectual discourse, joining the writer Arundhati Roy and others in the growing campaign for economic justice.

American Power and the New Mandarins was published in 1969 by Pantheon Books, whose editor was Andr� Schiffrin. Schiffrin was an unusual figure in the publishing world as someone directing a major publishing house which was open to radical social analysis and bold historical investigations. He recognized, in that year of continued escalation of the war in Vietnam, that Noam Chomsky was emerging as the leading intellectual critic of American foreign policy. And he wanted readers to experience the power of Chomsky�s thinking.

The essays in this book had various origins: a lecture at New York University, articles in the now-disappeared radical magazine Ramparts, essays in the New York Review of Books. What is common to all of them is a fierce attachment to egalitarian principles, an unsparing dissection of American imperial ruthlessness, and a devastating critique of American intellectuals, the �new mandarins� who remain subservient, openly or subtly, to the rulers of society.

None of Noam Chomsky�s political writing is abstract, theoretical, academic. It is always immersed in the reality of social struggle, his arguments meticulously documented nearly to the point of overwhelming his readers with information. One cannot read him without being awed by the breadth of his reading.

Undoubtedly the most famous of his essays in this volume is �The Responsibility of Intellectuals,� which began as a talk at Harvard University in June 1966 and appeared in the New York Review of Books in February 1967. This was no academic exercise. �We can hardly avoid asking ourselves to what extent the American people bear responsibility for the savage American assault on a largely helpless rural population in Vietnam�.�

Why was Chomsky, a world-famous philosopher of language, whose work on linguistics was often described as comparable in its field to that of Einstein in physics and Freud in psychology, writing about the war in Vietnam? Because, as he wrote in this essay, �It is the responsibility of intellectuals to speak the truth and to expose lies.�

That essay was certainly one of the most important pieces of writing to come out of the war in Vietnam. It appeared at a time when the American assault on Vietnam was reaching a crescendo � in 1966, 200,000 troops were on their way to Vietnam and the bombing of both North and South Vietnam was destroying villages, ruining the land, using the most deadly weapons yet developed for air war. Cluster bombs with their thousands of exploding pellets, �Daisy Cutters� which totally destroyed an area 300 feet in diameter, and B-52 heavy bombers were terrorizing the countryside.

The American people were still largely supportive of the war, but the press was beginning to report on the devastation caused by the bombing, and not just in North Vietnam, the enemy, but in South Vietnam, which presumably the United States was defending. Charles Mohr wrote in the New York Times that �few Americans appreciate what their nation is doing to South Vietnam with airpower � this is strategic bombing in a friendly allied country � innocent civilians are dying every day in South Vietnam.�

When Chomsky�s essay appeared, there were already demonstrations around the country against the war, but intellectuals were divided, some supporting the anti-war movement, some defending the war, others uncertain, or, if opposed to the war, cautious about expressing their opposition. By dissecting the argument of the intellectual apologists for American policy, and showing, by example, what honesty required, Chomsky�s essay was a sharp thrust at the conscience and sense of responsibility of hitherto silent observers.

How did Chomsky himself come to feel that responsibility? Why did he, instead of being content with his prestigious reputation in the academy, turn his mind and his energy to the war raging in Vietnam, to the bombing of peasant villages, the napalmed children, the hapless GIs sent halfway around the world to die for a cause no one could rationally explain?

No one can conclusively explain a person�s moral development by early experiences. But they must be taken into account as part of a complex mosaic of cause. Noam Chomsky grew up in Philadelphia in the years of the Depression, the son of immigrants, and recalls that as a boy he �saw police beating up women strikers outside a textile factory.�

At ten he became interested in the civil war going on in Spain, and wrote an editorial for his school paper on the fall of Barcelona. Perhaps it was Barcelona�s exciting, inspiring experience with anarchism in the first years of the war in Spain that led him at the age of thirteen to look in bookstores for works on anarchism, and then to a lifelong sympathy for anarchist ideas.

At the University of Pennsylvania he studied linguistics under Zellig Harris, went on to a much-coveted Junior Fellowship at Harvard, and in 1957, at the age of twenty-nine, wrote his revolutionary study of language, Syntactic Structures, in which he proposed that there is an innate capacity for language in all humans, a �universal grammar.�

The connection between his ground-breaking work in linguistics and his political convictions lies in his belief that there is a �fundamental human nature based on some instinct for freedom.� This idea underlies his long involvement in movements for peace and social justice.

I first met Noam Chomsky in 1966. I had recently come North from seven years of teaching at Spelman College in Atlanta and involvement in the southern movement against racial segregation. Noam and I found ourselves sitting next to one another on a flight to Jackson, Mississippi, part of a delegation from New Englang to investigate the mass arrest of black people in Jackson. That trip was the beginning of a long friendship.

He had already begun to protest against the war in Vietnam, starting in 1964, the year when large-scale United States intervention in Vietnam began. In the years that followed he became an indefatigable speaker at rallies and teach-ins. We shared a speakers� platform many times, and I soon became aware of his amazing capacity for retaining information and presenting it with great force and eloquence to his audiences.

But he was never content with intellectual work � with speaking and writing. In the great protest march on the Pentagon in 1967, Noam was arrested, along with many others. Afterward, he wrote about that episode, reproduced in this volume as �On Resistance,� as an example of the turn �from dissent to resistance,� to civil disobedience, but insisted that resistance to the law was only part of a spectrum of possible responses to injustice, and that the more moderate, less dramatic form, dissent, was also necessary.

That time of the Pentagon demonstration, Noam found himself in a cell with Norman Mailer, who, in his classic account of that event, The Armies of the Night, described his cellmate as �a slim, sharp-featured man with an ascetic expression and an air of gentle but absolute moral authority� who seemed �uneasy at the thought of missing class on Monday.�

In the spring of 1971 Noam and I were part of what still seems to me a strange little �affinity group� that traveled to Washington to participate in acts of civil disobedience � blocking the streets leading to the bridges over the Potomac � as a protest against the war. With us was the historian Marilyn B. Young, the former government expert Daniel Ellsberg (not yet revealed as the distributor of the top-secret Pentagon Papers), the biologist Mark Ptashne, the returnee from work in the rural villages of Laos Fred Branfman, and a few others. We did nothing heroic, accomplished little, but declared in this odd way our feelings about the war.

Noam and I were among the speakers at what I have called �the last teach-in� of the Vietnam War. It was the end of April 1975, and American troops were now out of Vietnam. But the United States was still supplying weapons to the unpopular and corrupt government of South Vietnam, under siege by a North Vietnamese army. The teach-in, at Brandeis University, was in protest against the continued American intervention. In the midst of the proceedings, a student came racing down the aisle with a dispatch in his hand, shouting: �Saigon has fallen. The war is over,� and the auditorium exploded in cheers.

After the war, Chomsky did not stop his relentless critique of U.S. covert and overt intervention in various parts of the world. When the Reagan administration declared a blockade of the revolutionary Sandinista government in Nicaragua, five hundred of us occupied the John F. Kennedy Federal Building in downtown Boston, and were arrested. Noam and I, and all the others, were charged under an ancient Massachusetts statute: �Failure to quit the premises.� That charge � �failure to quit� � could well describe Noam and indeed the whole protest movement in this country.

Since the first publication of American Power and the New Mandarins, Noam Chomsky, through his dozens of books and his hundreds of public lectures, has become recognized as the leading intellectual critic of governmental policy, the most influential spokesperson for the principles of peace and justice in this country.

Just one example of his pioneering work: Almost singlehanded, he brought to the attention of the country the horrors perpetrated on the island people of East Timor by the government of Indonesia, which was using weaponry supplied by the United States. That campaign took years, as larger numbers of people began to understand what was happening in that remote Pacific country.

Finally, after perhaps 200,000 dead, with continued resistance by the East Timorese, and more and more international attention, the United States withdrew its aid, the Indonesian government agreed to an election, and East Timor won its independence.

In this volume, the reader will get a sense of Noam Chomsky�s far-reaching political and historical interests � the civil war in Spain, the background for the Pacific War with Japan. But through all the essays, there is the insistent presence of the war in Vietnam, on which he turns his intellectual powers in such a way as to say to all of us: this is the responsibility of the intellectuals, to use whatever gifts we have � to expose lies and to tell the truth � in the interest of making a better world.

- Howard Zinn, 2002

Website: http://chomsky.nl/over-chomsky/12-howard-zinn-over-chomsky Website: http://chomsky.nl/over-chomsky/12-howard-zinn-over-chomsky

|