|

|  |

Aborigines accuse Australia of racism at UN

Michael Anderson - 02.03.2005 20:03

UN told Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders own and control 20% of the landmass of Australia

Aborigines charge Australia with racial vilification and genocide at UN

In a statement issued from Geneva, Aboriginal political activist, Michael Anderson, said today:

�NGO submissions to the UN Committee on the Elimination of all forms of racial discrimination (CERD) told of racial vilification and genocidal practices against the Indigenous Peoples in Australia.�

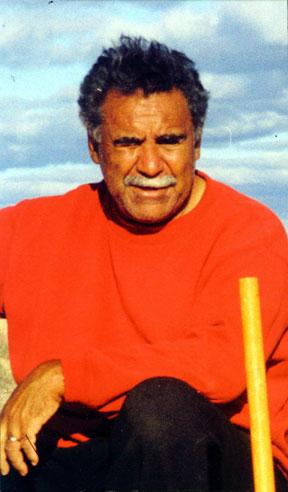

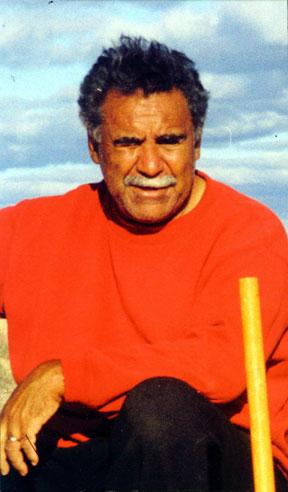

Michael Anderson on his sheep farm in Queensland.

Sovereign Union of Aboriginal Nations and Peoples in Australia (SUANPA)

GPO Box 1101, Canberra, ACT 2601

Ph: # 61 7 46250808 Fx: #61 7 4625 0804

Mobile +61 (0) 421 795 639

Email:  sovereignunion@hotmail.com & sovereignunion@hotmail.com &  ghillar@hotmail.com ghillar@hotmail.com

MEDIA RELEASE 1 MARCH 2005

UN told Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders own and control 20% of the landmass of Australia

Aborigines charge Australia with racial vilification and genocide at UN

In a statement issued from Geneva, Aboriginal political activist, Michael Anderson, said today:

�NGO submissions to the UN Committee on the Elimination of all forms of racial discrimination (CERD) told of racial vilification and genocidal practices against the Indigenous Peoples in Australia.�

The CERD commenced its session with open discussion addressing concerns for the lack of early warning indicators and early intervention measures that woule enable the UN to take effective steps to intercede. An Inuit observer from Alaska commented that he felt that it was not pure �coincidence� that this session on the prevention of genocide preceded the report of Australia.

Anderson is Leader of the Euahlayi and far western Gumilaroi nations in northern New South Wales (NSW) and southwest Queensland.

In an oral presentation to a briefing of CERD members, Anderson said: �Australia has a consistent pattern of policies and departmental strategies that have led to a high mortality rate, and the creation of a condition of life that will destroy the group in whole or in part. The life that our people are forced to live would not be accepted not tolerated by any other section of the Australian community.�

�Various CERD members were alarmed at the continuing high levels of Aboriginal incarceration. The statistics of Aboriginal people in the criminal justice system is an indicator of a disturbed society.�

Michael Anderson said: �The continued denial by Australian governments of recognition of Aboriginal custom, tradition and law/lore exacerbates the trauma, grief and loss being suffered by Aboriginal people. CERD members raised the question of the status of Aboriginal customary law to that of Western common law.�

Michael Anderson contends that recent court decisions in Australia give the impression that Native Title claims have no standing at all, if the common law gives preference to �past and future acts� by the western society.

Anderson goes on to argue: �The courts are failing to truly examine the correct definition of customary traditional law/lore, in favour of looking at Native Title from within a western framework.� He continues: �During the discussions on genocide it was agreed that a warning sign of genocide are dangerous theories on the incompatibility of co-existence.�

�An important aspect that could lead to preventing genocide is ensuring that there is a clear understanding of the historical memory. It is essential for the Australian states to acknowledge their collective participation in designing an assimilation process through eugenics and social engineering,� Michael Anderson concluded.

�Members of the CERD asked the Australian ambassador to the UN, Mr Mike Smith, to explain the difference between practical reconciliation and reparation. This was advanced to question what other measures are being offered to the people who suffered removal under past government policies and practices, since Australia�s report indicated that they do not favour financial compensation.�

UN told Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders own and control 20% of the landmass of Australia

The high-level Australian delegation led by Mr Smith, Australian ambassador to UN, told the CERD that Aborigines and Torres Strait Islander People own and control 20% of Australia.

The Pakistan representative, Mr Shahi, asked: �How much of this land is desert and swamp, as opposed to cultivatable and arable land ?� No details were given.

Mr Peter Vaughan, an Australian government delegate specialising in Native Title, informed the CERD that since 1998 the native Title Act as amended is working more effectively than the five years preceding these amendments.

Michael Anderson said: �Peter Vaughan misled the CERD by saying that in excess of 50 Native Title outcomes have been reached as opposed to five under the 1993 Act. What Mr Vaughan did not say was how many of these were consent agreements as against successfully litigated outcomes.�

In response to the Yorta Yorta People�s loss, the Australian government delegation informed CERD that they are well looked after in an agreement negotiated with the Victorian government. No details about the benefits were provided.

CERD sought a clarification of what continuing Native Title rights are left as a result of the Native Title Act and recent court decisions. One question was whether Native Title continues to be a common law right or whether the courts determine Native Title through codification as set out in the Native Title Act as amended.

The Australian delegation responded that despite establishing new legal frameworks Native Title remains within the common law.

Michael Anderson argues: �This is not quite the truth. The courts no longer give sufficient weight to traditional customary law/lore; instead judges place more weight on deciding Native Title within the Western legal framework, thereby lessening Native Title rights under Aboriginal customary law/lore.�

�I was amazed that this high-level Australian diplomatic delegation skimmed across the surface of accepting that the 1998 amendments to the Native Title Act were to provide a balance between competing interests of Native Title and the proprietary interest of non-Aboriginal land holders. They concluded that it was necessary to secure tenure for non-Aboriginal interests and that�s why they retained the right to negotiate and compensation for those affected, if it was felt that they had a high probability of proving Native Title.�

This, Michael Anderson said, clarifies for him and no doubt other Aboriginal people that the objectives of the amendments were absolutely racist in design and purpose.

�I wonder if the former Senator, Mr Harradine, and the Jesuit priest, Frank Brennan, can sleep at night?� asked Michael Anderson. �But what could else could we expect from a society that has its roots steeped in theft and criminality?�

`

ENDS

|

| Read more about: anti-fascisme / racisme | | supplements |  | | some supplements were deleted from this article, see policy | | The complete document | x - 02.03.2005 20:44

Submission to ICERD

Committee on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination

1-2 March 2005

Palais Wilson, United Nations, Geneva

In contradiction to Australia�s report to the CERD:

an Aboriginal perspective

by

Michael Anderson

Convenor of SUANPA

Leader of the Euahlayi and far western Gumilaroi nations

in northern New South Wales (NSW) and south west Queensland

This brief is in response to the 13th and 14th periodic reports of Australia due on 30 October 2000 and 2002 respectively covering the period 1 July 1998 to June 2002.

Introduction

[Paras 1-4] We contest Australia�s assertion that they are in fact operating in conformity with the ICERD and other Human Rights covenants.

Consultation with State and Territory Governments

[Para 5]

Most countries of the world do have a similar constitutional framework to that of Australia. Australia, however, constantly emphasises the need to respect the domestic sovereign powers of the States in accordance with the Federal constitution�s framework in respect to state powers. Unfortunately for Aboriginal Peoples the Federal government provides shelter for various racist state regimes to operate, arguing that it is their right as a democratically elected institution, to govern in accordance with the mandate given by their constituency.

The reservations made by the Australian government in respect to ICERD, ICCPR, ICESCR are in place to permit the States to operate racially biased and discriminatory laws. Furthermore, the reservations, which deal with the freedom of speech and expression, permit racist media commentary, which continues to infuriate Aboriginal people and the multicultural sections of Australian society. We insist that Australia must be influenced to withdraw their specific reservations to articles of ICERD.

I. GENERAL MEASURES OF IMPLEMENTATION

[Para 6-13]

Australia�s commitment to ICERD is severely undermined when the Federal Parliament itself can create laws that racially discriminate through suspending the application of its own Racial Discrimination Act (RDA). This is further complicated by the fact that Australia�s constitution has no appropriate clauses, which prevent Parliament from passing laws that may be detrimental to any racial group living within its borders. We therefore submit that any discussion about Australia�s violation of clauses of ICERD is purely academic, unless the United Nations take the appropriate action through their political influence to persuade Australia to take appropriate actions to change its course and its resistance to offering real and meaningful protections of Human Rights.

Human Rights Legislation Amendment Act 1999 (Cth)

[Paras 14-19]

It is our submission that whilst there are some very positive aspects to HREOC and its terms of reference, it is hampered and restricted when dealing with racist literature, albeit print or audiovisual media. It is also limited when dealing with the publication of racist material, particularly that which is published by major publishing companies. On the matter of funding we argue that HREOC cannot fulfil its responsibilities because of the restricted amount of funding allotted to its functioning. The appointment of Commissioners should involve people from outside the public service. Any appointment from within the public service will not provide the necessary objectivity required, thereby compromising its work.

Further reform of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission

[Paras 20-23]

We are unaware of The Human Rights Legislation Amendment Bill (No 2) 1999 being resubmitted for the Parliament�s consideration. The question to be asked is: Does the government intend to have this Bill resubmitted for a vote?

Human rights education

[Paras 24- 49]

In response to these paragraphs we submit that they are honourable objectives, however, all this effort will be a waste if Australia fails to rescind its reservation to the various Human Rights covenants and conventions. Since 9/11 in New York, there has been the development of some very frightening trends, which have given rise to what amounts to absolute paranoia through xenophobia. Whilst nobody tolerates aggression of any form we must maintain decorum at all costs. Any development of intolerance must not be permitted and must be outlawed through the appropriate Federal laws. A failure to do so will only permit an exacerbation of the xenophobia that is now so starkly obvious in our society. Defence of our citizenship in civil society cannot be guaranteed by aggressive offensive strategies.

II. SIGNIFICANT LEGISLATIVE AND POLICY DEVELOPMENTS

Anti-discrimination legislation and related developments

[Para 50-51]

What this report lacks is an identification of the problem areas identified in the CERD reports and what the government has done to address the identified problems.

[Paras 52-58]

The Victorian government has shown much stronger leadership in this matter than the Federal government because it goes further than the Federal Racial Discrimination Act 1975. It also reinforces the absolute need for the Federal government to rescind their reservations, which we have already mentioned.

[Paras 59-63]

It should be pointed out to this committee that as a result of the death of an Aboriginal man on Palm Island while in police custody in November 2004, the rage of the Aboriginal people has resulted in a number street marches, where various Aboriginal leaders have expressed their views. These views incorporate the anger and frustration being felt by the people and have resulted in certain incidences of people saying: �We have a right to defend ourselves from such aggression on the part of the police. This includes fighting with police in defence of our own being, if absolutely necessary. This calling was prompted by the coronial report into this man�s death, which concluded that he died in extreme pain.

Under the Anti-Discrimination Amendment Act 2001 (Qld), police and government agencies have now flagged their intention to arrest and charge Aboriginal leaders, they deem to be inciting confrontation and aggression, through self-defence. This reminds us of an era that we have previously experienced in colonial days of ruling Aboriginal People by �instilling terror� in the hearts and minds of the people.

[Para 64-71]

The State and Territories are beginning to take appropriate steps to ensure the protection of Human Rights in more areas. We commend the political leadership and all those involved, who seek to rid our society of the evils of racism and xenophobia. We await for the Federal government to find the political will and integrity, as promoters of Human Rights, to do the same. Saying is one thing, doing is another.

III. IDIGENOUS ISSUES

General policy

[Para 72]

It is the government�s submission to ICERD that as the Federal government they say that they are:

- taking a whole-of-government approach by involving all relevant portfolio Ministers and the States and Territories, working within the reconciliation framework set down by the Council of Australian Governments; (see paragraphs 92-95 for further discussion)

On the surface this appears to be a noble act by the Australian governments, however, it is important for us to highlight the �devil in the detail� behind this sort of initiative. The actual operations in the grassroots communities and on the ground are something very different. It would take far too long for us to detail the negative aspects which far outweigh the positive, but we would be only to happy to advance discussions further if required by the CERD or the individual members.

- increasing the focus on individuals and their families as the foundation of functional communities;

The Australian governments, Federal, State and Territory, continue to blame the victim. There is ample evidence within various areas of university studies, which clearly demonstrates that the disunity and dysfunction that exists within the Aboriginal communities across Australia are the direct result of past governments� policies and practises. To continue to deny the need for reparation and appropriate reconstruction programmes will only serve to perpetuate disunity and dysfunction permitting its passage as an inter-generational saga. (Eg. See works by Ernest Hunter, James Cook University, Townsville, Qld)

We are encouraged by this as an initiative, however, real and positive job creation programs are required. This does not mean a revisit to a 1970s programme of relocating families from their own traditional lands to foreign cities, under the guise of being placed in situations where education and job opportunities are significantly greater. The 1970s programme was an abject failure. Australia�s societal planning falls a long way short of placing any emphasis on the decentralising of industries and/or the creation of industries beyond the scent of the sea. The Community Development Employment Programmes (CDEP) are terminal by nature. There is no progressive development that can lead to self-reliance and independence, nor progression through a career path. At present some of these CDEP groups, i.e. work for the dole, are abused by pastoralists and some industries in order for them to gain access to cheap labour, allowing them to maximise their profits.

-strengthening leadership, capacity and governance:

This is an honorable initiative but one that raises much concern for our grassroots leadership. This concern focuses primarily on the weight that will be placed on government approved and certified �leaders� through this programme, in preference to born grassroots leaders. That is, greater weight will be placed on the opinions of the �certified leaders� as opposed to those of the uncertified grassroots leadership. This is a most vile and disgusting piece of planning because it will only serve to divide the Aboriginal leadership into the educationally accepted �leader� from the uneducated impassioned grassroots leader, who purportedly will be motivated by emotion for his/her cause, rather than rational objectivity. Our true Leaders are born, not educationally molded into acceptability by the dominant society.

addressing the debilitating effects of substance abuse and domestic violence;

We refer to our previous discussion on �blaming the victim�. We argue that the dilemma faced by Aboriginal Peoples is multi-faceted. The intergenerational trauma resulting from past government policies and practices has lead to this dysfunction.

We cannot place enough weight on our assertion that: forced and unacceptable marriages; removal of our children; being relocated from our traditional homelands and forced by confinement never to return; being institutionalized and imprisoned on government Aboriginal mission stations under the control of a government appointed tyrannical commandants; dominant church institutions, where we were incarcerated, for simply being Aboriginal; providing certain families with Exemption Certificates, which deemed them �white� thereby by separating them from their families by a class system; being denied the right to speak language; being denied the right to express and participate in religious practices and spiritual observances of our own; being divided by a caste system, have had serious repercussions for Aboriginal people then and now. The governments, for their part, refuse to accept that these and other governmental restraints have, and continue to, create the dysfunction that now leads Aboriginal people into an unacceptable and anti-social behavior, as is being observed and interpreted by the leaders of the dominant society.

To demonstrate the level of despair and hopelessness I take the liberty of citing a statement made to me by my cousin at my Dad�s funeral. I was asked by my cousin to go and get drunk as part of the funeral wake. My response was: �Why do you want to get drunk?� His reply was simple: �I�m happy when I�m drunk. Life is so boring and hard to face when you are sober.�

It is our submission that all levels of Australian government must redirect their energies, departmental objectives and goals to address the continuing traumatised minds of Aboriginal people. To maintain a society of people burdened with traumatic lives and poverty cannot and will not contribute to locating the solutions for these problems in the future. Australia must admit to the wrong doings and work with Aboriginal people to redress the trauma and facilitate culturally appropriate measures and support programmes that will lead to meaningful healing.

The severity of domestic violence increased after the governments, in their alleged wisdoms, commenced a programme of resettlement in the mid 1970s. The objectives were to increase to individual opportunities for Aboriginal people. Instead, this programme separated Aboriginal people from their extended family support base, and the individuals, who took up these options became isolated, through the process of dislocation and �pepper-potting� within the dominant society, which remained principally racist. This racism is highlighted by statements made in provincial cities, where they refer to areas within their towns or cities, where there is a congregation of Aboriginal residents, as �Vegemite Hill�, �The Broncs� or �The Ghetto�.

increasing opportunities for local and regional decision-making by Indigenous people, and improving program coordination and flexibility to respond to local needs;

The establishment of �community working parties� [see also discussion of COAG paras 92-95] continues the practice of disenfranchising the less vocal and minority Aboriginal families from the decision-making process. In some cases, this means that the extended family groups of other nations, who were relocated during the round-up in mission days of mid to late twentieth century and 1970s, are now dominant in numbers over the minority traditional owners. The design and control of community-based programmes does not necessarily translate into appropriate and effective measures of dealing with social injustice and the needs of the community. The process of selection for the community working parties is neither democratic nor just. It is a case of introducing a foreign system of governance. In other words, Australian governments and its bureaucrats continue with their zeal to force a square peg into a round hole. This effectively eliminates real and meaningful decisions being made the traditional owners who have the traditional and customary responsibility for such matters in respect to those lands and territories.

We argue that �special measures� on the part of government fly in the face of governments, particularly when one considers free flowing and clean drinking water; developed and functional sewerage systems; appropriate housing; health services; and the provision of public utilities such as communication systems and electricity are the basic and fundamental right of all Australians. When dealing with the provision of these societal necessities to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, why are they classified as �special measures� and are being offered to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, as though we are within the marketing system. We determine that the government�s establishment a programme of reward-or-effort when providing for community services and needs is misguided and racist in the extreme.

- improving access to mainstream programs and services, so that Indigenous-specific resources can be better targeted to areas of greatest need, particularly to areas where mainstream services do not reach.

This debate within white society and their governments has been going on since colonial invasion. One question that can be asked is: �Why, as members of the Australian society, do we continue to lag behind in service provisions? If we a are denied the basic rights of running water and electricity to name a few, why were we left out of the planning processes and our needs excluded?

Reconciliation

[Paras 73 �79]

Reconciliation is not an accepted objective amongst the grassroots people in the Aboriginal communities. In fact, the cynical comments of the grassroots leadership when they speak of reconciliation are: �Oh, that�s that Canberra mob (group) all trying to be friendly with each other.� The other comment is: �They are passing a law so whitefellas and blackfellas can talk and mix with each other.

In 2000, the Jordanian representative on ISESCR posed a question to the Australian delegation: Is your reconciliation process an admittance and recognition of a war that had gone on in Australia? Grassroots communities will argue there has always been confrontation with authority in private and public sectors since the time of invasion. Confrontation and resistance is almost the norm in every Aboriginal community throughout Australia. The incarceration statistics that are provided in other NGO reports to CERD reflect the level of incarceration and represent an indication of Aboriginal resistance to oppression through non co-operation and civil disobedience. In order to put this level of confrontation and resistance down, ordinary non-Aboriginal citizens and their civic leaders constantly call for the tightening of laws to address what is popularly referred to as a break down in law and order. It is our contention that the process of reconciliation is void of purpose and substance. True reconciliation can never be achieved without a recognition and acceptance of the wrong doings by governments and the introduction of laws that guarantee that it will never happen again. This action must have the precursor of a public apology.

Reconciliation Place in Canberra, which is referred to in Australia�s report, is a feeble attempt at trying to appease the minds of a section of the Aboriginal community. It is also a very poor attempt to show to give the Australian public the impression that Australia acknowledges her wrong doings. Its design, however, is indicative of the continued process of denial. This denial is reflected in the design of Reconciliation Place where the imagery of very selected pieces of history is hidden away in a small walk-through tunnel while the grounds above are bare and covered with manicured turf. Without stumbling over a few �slivers�, which are at the entry point to this hidden story, one would deduce from first impressions that nothing is there.

The Living in Harmony concept is a far cry from the reality of the grassroots existence of Aboriginal people in the isolated rural remote communities. The racial tension and conflict that exists in these centres is at boiling point and can in no way be described as places where people live in harmonious relations.

Addressing Indigenous disadvantage

[Paras 80-82]

While the government admits to an unacceptable level of infant mortality they are still not able to say that these deaths are now on par with the rest of Australian society. We acknowledge their stated methods to rein in the high mortality rate and we eagerly await the statistical outcomes over the next five years. What is not stated, however, is the dramatic increase in teenage and adult mortality. Our assessment of our communities� mortality suggests that in the next ten years the majority of our elders will be aged between 45 and 55 with the predominant age of our population being between 12 and 25. When we speak to the elders who are left, we often hear them say: �Our people are dying from nothingness.� The frequency of funerals in a week in some of our communities throughout Australia, means that we are attending between 2 to 4 funeral services a week, more in some cases.

We also express concern for Aboriginal babies. Within the Australian Capital Territory, for example, it is widely known that Aboriginal infants� birth weight is well below average. This contributes to a health deficit before the child leaves the hospital grounds. This is also the case throughout most centres in Australia. Problems of ill health are exacerbated by the extremely low socio-economic status of Aboriginal people and the devastating poverty levels of Aboriginal communities in rural and remote areas, whilst most city-based Aboriginal people are forced to live in ghetto-based housing estates, which are run by the State. It should also be mentioned that in these areas there is a high police presence, which constantly contributes to confrontation.

Health services:

The Federal Government is in a better position to offer improved health services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across the Northern Territory, because of the Commonwealth/Territory relationship. The States on the other hand provide services through the mainstream health care services, but in Aboriginal communities, for example, along the Barwon-Darling river system in NSW their remoteness and paucity of health services require individuals to travel, or be transported, to centralized regional provincial cities. The difficulties here are not necessarily the service itself but rather the economics. Individuals and/or their children, who are hospitalized, almost inevitably find themselves alone and without the support of their own family members. Families are often unable to accompany the ill because of the distance and cost. Invariably the patient is left in these centres to make his or her own way back home.

One significant point that must be raised here is that most Aboriginal women are forced to travel outside of their country to give birth to their children. The creation of the birthing centres that exist in the Northern Territory are not on offer to Aboriginal people in other States. In the main, health services are being mainstreamed and, as a consequence, they are not consistent with specific Aboriginal needs, which were advocated in the Aboriginal National Health Strategy, which was never heeded implemented.

between 1992-94 and 1997-99, Indigenous death rates for infectious and Parasitic

diseases fell from between 15 to 18 times the non-Indigenous average to

between 4 and 5 times;

The report from the Australian government to CERD, commenting on improving Aboriginal health through erasing infectious and parasitic diseases, requires a greater explanation. For most Aboriginal people, illness through infection and parasites has not been fully explained to the people and their communities. If infectious diseases and parasites are so great that it warrants special mention in a report of this kind, then it is incumbent on the government and the authorized health departments to inform the communities and work with them on specifically designed proactive programmes to eradicate the parasites and the infectious diseases. We call on the Australian health authorities to make this information widely known to the Aboriginal communities. Furthermore, we ask them to define and identify the exact nature of the parasites and infectious diseases and that this information is translated into the appropriate languages.

-the proportion of Indigenous children who stay on at school through to Year 12 rose

from 29 per cent in 1996 to 36 per cent in 2001;

It is fine for the Australian government to produce statistics with respect to improving retention rate within the school system, but what is not reported is the scholastic achievement levels. Our concern is that many Aboriginal children in their formative primary years go on to senior level without the ability to read or write. In the majority of cases their mathematical achievements are almost non-existent. We consider that Aboriginal educational achievements within the public schooling system are a disaster. Citing statistics and funding levels does not help students to realise their true potential.

The poverty level and dysfunction within the communities exacerbates the child�s ability to learn from and within the system that has demoralized their people. Too often we hear Aboriginal children say: �We only learn about white people and not about us. We were here before Captain Cook.� Special mention needs to be made of the fact that the Howard government demolished the bilingual programme for a few Aboriginal language groups. Talk-back media protagonists conducted public discussions on national radio supporting the government cut-backs by arguing that �we are all Australians�; why should we bother spending Australian taxpayers dollars to support language programmes that only a few can speak. These protagonists always argue we are �one Australia� and English is our language. The high level of school absenteeism throughout country Australia reveals a rejection of the existing school curricula and purpose. I come from a country town called Walgett, where there is a predominance of Aboriginal children attending school. Where the high school population numbers represent between one hundred and one hundred and fifty Aboriginal students, on most days less than 80% are present. From my experience and knowledge the same can be said for the majority of Aboriginal towns in western and northwestern NSW. The statistics presented in the Australian report are questionable. It is important for us to make special mention of the fact that the majority of Aboriginal children attend the State public school system, which is supposed to be free, but this year the NSW Department of Education acknowledged the level of poverty suffered by the children who attend State schools by providing at the beginning of the 2005 schools semester a cheque in the amount of $50 for every child to assist them in purchasing school stationary and/or clothing. Aboriginal children, who seek to attend university invariably require a level of funding that is beyond their reach. Topics, such as Maths I and II, Biology, Chemistry, Physics, English Level I, General Science etc., attract fees, which are beyond the reach of the ordinary Aboriginal student. This effectively means that the Aboriginal student receives the very basic levels of education. Their achievement in their final graduation level from High School means they may be well placed to become plumbers, mechanics and carpenters if this is within their reach. The statistics offered by the Australian government for post-secondary studies represents an increased number of mature-aged students returning to study.

the number of Indigenous students undertaking post-secondary vocational and

educational training virtually doubled from 26,138 in 1995 to 58,046 in 2001;between 1 July 1999-30 June 2002, over 5,920 Indigenous people were placed in jobs

through the Indigenous-specific Wage Assistance program, and 11,473 Indigenous

jobseekers were assisted under Indigenous-specific Structured Training and

Employment Projects;between 1995-2001 the number of Indigenous people commencing traineeships and apprenticeships increased significantly from 1,320 in 1995 to 5,950 in 2001;

Again the statistics look good, but the reality is very different. Mainstream, private and public sector industries applaud the opportunity to gain subsidized staff. Unfortunately, the position usually becomes redundant at the end of the subsidy. There is no security in the workplace, nor is there opportunity for them to pursue a career path, all because the non-Aboriginal controlled industries refuse to obtain their services in the majority of cases. What needs to be asked of Australia by the CERD is for a breakdown of the number of Aboriginal people who are tenures or employed fulltime at the end of this subsidy period.

in 2001, there were 4,321 Indigenous students enrolled in a university bachelor

degree, the highest enrolment numbers on record;

This point is especially noteworthy because it demonstrates the eagerness of Aboriginal people to be given a fair go. If those preparing the statistics were to compare the ratio per capita of the number of Aboriginal people going to university with the actual achievement of degrees, one would see that Aboriginal achievement far exceeds that of the non-Aboriginal population. In fact, if the government had not changed the criteria for funding for tertiary programmes, through means testing and financial cutbacks, the figures in their reports would be much greater. If the Federal, State and Territory governments had not entered into a programme of absorbing Aboriginal university graduates into the public sector workforce, the statistics would show a significant number of university qualified Aboriginal people unemployed and possibly on a CDEP programme.

Our remaining Elders hold another view. The government purposely absorbs our intelligencia to keep them away from locating solutions for the grassroots problems and many of our young people find themselves assimilating through economic commitments. In the previous discussions we said that the figures relating to Aboriginal participation in tertiary institutions do not differentiate between the number of Aboriginal youth coming from high school direct to university as opposed to mature-aged entry students. Again we emphasise the need for Australia to identify the true statistics, rather than compiling a selection of statistic, which do not reflect the true situation.

Aboriginal graduates have little alternative but to take a position in the public sector workforce because job opportunities in their own community are virtually non-existent. If they want to work in their own community organizations, the maximum rate of pay that is funded through government grants amounts to a maximum rate of pay of $45 000. This rate of pay is the minimum rate and starting point for entry into the public sector workforce.

93 per cent of discrete communities in 2001 had access to electricity compared

to 72 per cent of those communities in 1992; and

73 per cent of those communities in 2001 had higher-level sewerage systems

compared to 55 per cent in 1992.

We are at odds with these two statements, because we were not aware that providing sewerage and electricity to Aboriginal communities is deemed by government to be a �special measure�. Denial of basic public utility services to Aboriginal communities is a measure of the level of administrative negligence and planning flaws. We submit that there is much to do to correct these disparities.

-$2.5 billion dollars on Indigenous-specific programs (2002-03)

We are alarmed that the Federal Government of Australia should put up, as an indication of their sincerity when dealing with Aboriginal disadvantage, a dollar sign. If the Australian government seeks to use the amount of dollars appropriated as a sign of their commitment to address disadvantage, then it is our right to ask: Why do we continue to have this high level of disadvantage, when in the past thirty six years Australian governments have appropriated in excess of $50 billion for a reported population demography of 400,000 people. And yet they continue to appropriate large amounts of money to address the inequalities and disadvantage that continue to linger throughout Aboriginal Australia. We submit that it is not money alone that is required. The need is to have a genuine transfer of responsibility into the hands of self-determining Aboriginal communities. The people must own their own programmes and services. We have the right to provide our own services without hindrance, prejudice, qualifications or restraint. But we should not pursue the path that has been decided upon by the government when they put up regional pilot programmes, such as that agreed to by the government with the Murdi-Parrki in NSW. My community and nation are situated within this region. As a People who are supposed to benefit we have never seen any agreements that have been entered into, nor were consulted as a community in general on the terms of the pilot programme. I cannot inform the CERD of any of the terms of this project, because the people have no knowledge of them at all. The only ones who have the knowledge are those who are administering them.

It is appropriate for us to say that of the $2.5 billion dollars allocated includes a significant amount specifically designated for the Attorney General�s office to fund the white landholders� legal costs to challenge and defend their interests against Native Title claims.

In all, Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) fails to inform the public that, of the Federally appropriated funds for Aboriginal Affairs, less than eight cents in the dollar is available at the grass roots level to combat the inequalities and poverty. The remaining 92% props up bureaucratic and consultant industries.

Northern Territory: We are at a loss as to why the Federal government chooses specifically to talk about their efforts in the Northern Territory, while dismissing the need to treat the other States on an individual basis.

Families and communities

[Paras 83- 87]

In relation to these paragraphs we have provided our statement above. We only seek to add that the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) as a functional entity is no longer. It is now replaced with the National Indigenous Council (NIC). This Council consists of government selected acceptable Aboriginal individuals. The abolition of ATSIC and the appointment of NIC is an insult. The Howard Government�s support for imposing democratic processes in foreign cultures represents a blatant hypocrisy of standards. It seems to us that imposition of the democratic process is only considered correct and just by governments, if it provides support for their own ideals and ambitions. In Australia, Aboriginal people are denied this process because the Federal, State and Territory governments are in a better position to exploit us. We are only a domestic numerical minority, whose ability to threaten political change and economic stability is absolutely limited.

[Paras 88-91] Bringing Them Home Report

We are concerned that the Federal government has failed to work with State and Territory governments and church institutions to achieve agreement between the parties to provide open access to the records of each of the families affected. It is contemptuous for the NSW government to suggest, in a recent statement, that the provision of open access to the records, for the families concerned, is not in the public interest. We are in contact with many members of the Stolen Generations and others, who were not taken, but confined to the government controlled mission stations. In many cases, those committed to church institutions were indeed the offspring of wealthy graziers and farmers, doctors and lawyers, civic and business leaders, to whom their mother was indentured. Being given this knowledge by the people concerned we can understand, but not condone, why some children were taken by government authorities and church institutions without any formal records being kept.

I can speak personally of how government officials have falsely misrepresented the numbers of Aboriginal people affected by government laws of removing Aboriginal children from their families. My grandmother was abducted from the school at Angledool in 1914. The same fate fell upon her six siblings. When we searched the government records we could only locate government documents relating to the first three taken. Her four other siblings were never recorded. Our only knowledge of them being taken are the stories by their peers and their own personal testimonies. Fortunately, we were alert enough to make sure that they told us their stories. This is how we learnt what properties they were placed on and the name of the farmers concerned. During this research we also found reference to other Aboriginal people, who were taken. The mistake made by government was to refer to them as spouses of an Aboriginal person.

Governments are insistent in their desire to protect the identities of the birth parents, for fear that the Aboriginal progeny may lay claim to any inheritance that they may be entitled to. We maintain that a government apology may create liabilities for governments resulting in some form of compensation, instead we argue that it is the former concern of bloodline that dictates their hardened resolve on this matter.

The comment by the Australian government that they have chosen to assist Aboriginal people to reconnect with their cultural ties would have a reservation to this objective. That reservation would be that any cultural knowledge, albeit true ceremonial and spiritual education and knowledge, would negate any right to assert Native Title rights and interests. In any case, under the Mabo judgment any revival of Aboriginal traditions and customs would automatically be denied, as Brennan CJ ruled that any revival of Aboriginal traditions and customs can not be used to assert continuing Native Title rights and interests. This conclusion meant that, in the opinion of the High Court, any traditional Aboriginal customs and ceremonies and or religious observances could not be reconstructed and used in Native Title claims. The High court�s reasoning is an absolute denial of natural justice and is racially discriminatory in the extreme. We ask: Where would Christianity and English literature be, if a court denied their revival? Such revival based on the Mabo decision would be outlawed. Such a stand on the part of the High Court and reinforced by the national government is totally unacceptable. Even the West�s Christianity permits evangelism!

Council of Australian Governments initiatives

[Paras 92-95]

The Council Of Australian Governments (COAG) arrangements and initiatives described in this report are not known by the broader grassroots Aboriginal community. These set objectives, as described, are generally only known to the participating agents. The community working parties that we spoke of earlier are the agents through which these programs are being introduced. As a participating representative on one of the community working parties, I and my colleagues were never made aware of the COAG arrangements that are described in the Australian CERD report. It is our view that the Aboriginal communities will be forced to accept these programmes. In the past the bureaucrats have been asked to explain the policies. They invariably say that the aims and objectives and details of the programmes can be found on the Internet! There are not many Aboriginal people throughout Australia who can access the internet, especially if you are living in a rural or remote community.

As it stands the COAG participants, who continue to progress the agreements without true and informed consent of the targeted group, deny due process and natural justice. This action is indicative of the dictatorial approaches that have always pervaded the administration of Aboriginal Affairs. The sad irony is that should the programme initiatives fail, Aboriginal communities are blamed for wasting good taxpayers money.

Land rights and native title

[Paras 96-97]

It is important for the CERD to ask the Australian government to dissect the land ownership percentage, so as to gain a true picture of the amount of land transferred into the ownership of Aboriginal Peoples through the Native Title Acts� processes. For us in NSW, we can say that since the Native Title Act came into existence in 1993 to the present day in excess of $50 million has been channeled though the Prescribed Body Corporate (PBC) and its total yield of land ownership for its efforts amounts to less than 10 acres. The greatest portion of land held in trust for Aboriginal People came from the Land Rights Acts, pre 1993.

The �Prescribed Body Corporate� corporation in NSW takes the form of a partially authorized Prescribed Body Corporate pursuant to 1993 Native Title Act as amended, but it lacks the legal right to authorize traditional land claims. That is, no land claim can be registered in NSW without the full authorization of every member of the Native Title claim group lodging the claim. Even the logistics are beyond the means of the impoverished Native Title claims groups. The limited funding from NSW Native Title Services, the selected Prescribed Body Corporate, severely restricts Aboriginal Peoples� ability to convene the type of meetings, which could possibly facilitate what is deemed to be a properly authorized Native Title claim. This could amount to anywhere between $50 000 to $150 000 per meeting for one claim group. Under the 1998 NTA Amendments, a complete genealogical study of every family member of the whole nation is required. The impracticality of such a procedure guarantees failure even before a claim can be lodged. Not having the NSW Body Corporate properly authorized by the Federal Minister denies the Native Titles Services the ability to authorize claims, without having to go through the absolutely restrictive process of nation authorization. (For further discussion see Paras 109-116)

The processes for claiming land under the NSW State land rights regime is a restrictive process. It confines the Land Councils to claim only Crown land that is deemed to be unoccupied and unused. There remains outstanding in excess of 30 000 claims to various parcels of land in NSW that are yet to be dealt with. These claims under the NSW 1983 Land Rights Act cannot be proceeded with until traditional owners have lodged their claims under the Federal Native Title Act and a determination is concluded.

The belligerent stand by the NSW government, on the issue of Native Title, demands that a proposed Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) is negotiated in preference to litigation under NTA. Additionally, the NSW government will not contemplate consenting to Native Title, which permits them to dictate the terms for any ILUA. This is not acceptable for us, even though we seek to resolve this matter in an expeditious fashion, considering our claim has been sitting for the past seven years.

As a precursor to any ILUA, the NSW government has said that we must first agree to with drawing our existing Native Title claim and that we also agree not to submit a further claim for five years!

The NSW government has also proposed to the Euahlayi that no land will be transferred to traditional owners. Instead, should any land be transferred it will be vested in the NSW State Land Council, who have already abdicated any responsibility for dealing with Native Title matters. Traditional owners will only have the power to sit on a board of management, which will consist of other Aboriginal people not necessarily traditionally connected to the said lands. This approach is an absolute denial of traditional owners rights and responsibilities, which is in direct contrast to the Federal government�s assertion that the NTA 1998 amendments preserve and protect traditional Native Title rights and interests.

In concluding this point it was our understanding that the purpose of the Indigenous land Fund Corporation was to facilitate land acquisition for those Aboriginal people displaced under past government relocation regimes.

For any government to demand contrary land ownership practices shows an absolute lack of respect for pre-existing Aboriginal rights and interests. To suggest an offer of settlement of the nature described previously is an absolute contradiction of the continuing traditional laws and customs within our traditional Aboriginal society. ILUAs which demand land grants on the proviso that other Aboriginal people be included, particularly if they have no traditional ties and relationship to the land and the claimants, are against common decency and respect.

Indigenous Land Fund and Corporation

[Paras 98-101]

The Indigenous Land Fund (ILC) was set up for the purpose of acquiring land for those Aboriginal persons who could not succeed through the Native Title claim processes. Since its inception the ILC has acquired a number of properties and lands throughout Australia. Unfortunately, many of the traditional owners were duped into believing that they would take physical possession of the land, whereby they could resettle their group and establish Caring for Country regimes and economic enterprises. They soon found that this was not the case. With the exception of a few, the ILC has retained control and management of these lands and has made limited gestures to provide financial benefits to the traditional owner groups. Moreover, the ILC in its administration of these lands, has created a great deal of division within the Aboriginal community, by arguing that it was necessary for expensive genealogies to be conducted in order to determine who the true traditional owners of these lands are.

It is with regret that I have to say that it is from personal experience, Aboriginal people who were forcibly removed from their traditional lands over one hundred years ago are now in conflict with traditional owners. Their arguments are that their parents and grandparents (in some cases) who were born in these lands, also have a right in these lands. This problem has contributed to a lot of dissention and animosity in Aboriginal communities and no-one gets the land.

This confusion has created uncertainty and unpalatable division. It is vital for the State and Territory governments to furnish records of family names and places of those who were dispossessed and relocated under past government regimes. This will contribute to a more precise understanding of where people traditionally come from. This may contribute in the long term to a more successful approach by the ILC. The ILC�s success can be enhanced by acquiring land for those persons displaced. This we submit is obligatory on the part of, not just the ILC, but also State and Territory governments.

The ILC,for its part, must make every effort to transfer title deeds and management of all acquired lands to traditional owners within as short a period as possible. They can not continue to practice land purchase and put traditional owners names and/or their corporations on the title deeds without handing over control.

Another problem with the ILC is that of the appointment of corporate members, who have personal biases or differences with Aboriginal people and/or their communities.

As a member of the Euahlayi nation and its leader, I can affirm that the personal bias of the NSW representative against my Native Title claim group (the conflict is personal) and it is this personal conflict that prevents him from maintaining objectivity when it comes to land purchases in our area. On the one hand, he supports land purchases in the area, but will only support land purchase for other groups, no matter how demanding the need. Unfortunately, in our case, the ILC has purchased land which contain sacred sites, over which we have full responsibility and jurisdiction under our custom tradition and Law/Lore. The ILC has transferred these lands to Aboriginal people who do not have traditional connection and as a consequence economic considerations are their priority and it is this objective, on their part, which sees them disrespecting our sacred place and the Stories for economic gain. This has caused much anxiety and concern for my People and we are without power to alter these peoples� economic ambitions in favour of protecting and respecting our sacred places. Our complaints to the ILC fall upon deaf ears.

From our experience and our communication with other nations, land acquisition by the ILC fails to meet our needs. The administrative processes of the ILC and the unwillingness of the senior ILC administrators to talk to traditional owners promotes failure and loss of heart, which is leading to a �condition of life which will destroy the group in whole or in part�. Sadly, we have no appeal process.

In conclusion, what needs to be identified is the dictatorial approach that ILC has towards land transfer and management of most of the acquired land.

Land Rights

[Paras 102-104]

Aboriginal Peoples throughout Australia have acquired interest in more land holdings under the State and Territory Land Rights Acts than we can ever expect to gain through the Federal Native Title Act 1993 as amended. Unfortunately, vast tracts of these lands are deserts or swamps. In fact, we argue, that if it were not for State governments responding to large scale Aboriginal protests for Land Rights the Australian government would not be able to boast any major land holdings by Aboriginal people at all. We are now faced with State and Territory governments reviewing and altering existing Land Council structures through amendments to existing State and Territory legislation. These pending actions on the part of governments are causing great anxiety and uncertainty for Aboriginal people.

On the question of Native Title the achievements in Mabo and Wik were not achieved by the Federal Native Title Act. In fact, it was these two very important High Court rulings that literally forced the Federal government to legislate, in order to protect white land interests at the expense of Aboriginal interests. The 1998 Amendments were in response Chief Justice Brennan�s guide in Mabo as to how governments had the legal authority to legislate away any rights and interests Aboriginal people may have in land, without having to pay any form of compensation. The Federal government gives a brief description of consensual and binding agreements on future acts through negotiated Indigenous Land Use Agreements. Our experience in NSW, however, outside of the Byron Bay agreement, finds the NSW government excluding any discussion on future acts. The NSW State government totally ignores any right to negotiate because they have already concluded, in their minds, that there are no Native Title rights and interest existing in NSW. Therefore, there is no need to continue with the process of the Section 29 notice with respect to the right to negotiate.

Indigenous Land use agreements (ILUAs)

[Paras 106-108]

The NSW government, being influenced by the previous set of circumstances, has suggested to us, the Euahlayi, that our clan claims will not succeed through litigation. Their offer to us is to conclude an ILUA, where certain provisions and concessions will be made on their part. But they also seek from us a precursor to any agreement, namely, that we agree to withdraw the Native Title claims and agree not to lodge another claim for five years! Having said this to us, they then advised us that there will be no land transfers to the traditional owners. That is, any land negotiated by us for our clan groups will be divested to the NSW Aboriginal Land Council. The Land Council shall be the holders of the deeds and titles, for and on our behalf, while we may have use of the land, providing we agree that other members from others clans and nations shall have equal authority in respect of the control and management of these lands.

Secondly, they submitted that there will be no form of any financial compensation. Further, the government says they may agree to facilitate for us to obtain positions on advisory and governing boards in relation to waters, nature conservation, land management and National Parks Management Boards, as they relate to lands we currently have under claim. We do not accept this tokenistic proposal.

We are advised if we seek to pursue better outcomes then the NSW government will force us to continue with our litigation. Based upon the Federal Court judge�s comment to this date, we will not succeed based on the present information submitted to the court. It is this comment that provides the impetus for the government to take a hard line stance in its offer. Further, the NSW government has indicated to us that any application by other parties to have this matter struck out will not be opposed by them.

The Prescribed Body Corporate in NSW, Native Title Services, continually refuses us any financial assistance, because they argue that recent High Court conclusions do not support clan-based claims and they argue that it futile and a waste of money to support these claims. It is an irony that the High court decisions in recent cases support on the one hand, clan estates within the broader nations, but will judicially deal with clan-based claims by themselves.

Developments since amendment of NTA

[Paras 109-116]

In their submission to CERD the Federal government talks of the 10th anniversary of the High Courts ruling in Mabo. They have suggested that since the Mabo decision we have seen a paradigm shift in the Australian communities� attitude to Native Title. They then add that this profound change to Australian law has been recognized and protected under the NTA. We ask: What does this mean? Our experiences in country Australia are that white landowners and civic leaders continue to maintain an antagonistic attitude towards any talk of Aboriginal land rights. In fact, this antagonism has increased significantly in the last ten years. The profound change to the Australian law, from our point of view, has been the 1998 amendments, which have now provided the courts with a set of statutory laws to severely undermine and, in most cases, deny Aboriginal land rights.

We are disturbed that the Federal government�s report to the CERD is only to 2002 and not beyond. If the Federal government were to report the situation as it is at this point in time, they would be obligated to inform the CERD that the Yorta Yorta people of Victoria and southern NSW have been deemed by the courts to have had their Native Title washed away with the tide of history. The Aboriginal criticism of this finding is that a white farmer�s journals was given greater weight as evidence over and above that of the oral evidence presented by the Yorta Yorta Elders.

In this case, various people were concerned that the presiding judge, Justice Olney, had a vested interest in his decision, that is, his family have vast pastoral land interests. We assert it was incumbent upon him to identify his vested interests, or, better still, he should have disqualified himself from hearing the case. There were a number of other cases that the government referred to in their 2002 report to CERD, which suggested that there were other High Court hearings and reserve judgments still outstanding. One such case was the West Australian Ward case, or as it is called the Miriuwung Gajerrong case. Whilst the court held that Native Title did exist, the court decision was full of reservations and denials. (see other NGO submissions for further discussions and details.)

Another decision was handed down in 2003 was Wilson v Anderson (I am the Anderson in this case) on the issue of whether Native Title continues exist on 42% of the lands of NSW. The High Court held that the NSW Western Land Act of the 1950s created grazing leases that equated with freehold. The court considered that Western land, by being equated with freehold title, meant that the graziers gained an exclusive right to the lease. That is, the lessee had an exclusive right as against all other interests. We now argue that the court in making this decision corrected a faulty past history, because there is nowhere else in the world where land leases are as extensive as those in the various parts of Australia. It should be noted that these leases were originally granted to white squatters who went beyond the �Limit of Location� and in doing so were indirect violation of the government�s orders. So great were their connections to the aristocracy that they were able to form themselves into a political entity known as the Free Traders Association, which is now recognized as the liberal party of Australia. The decision in Wilson v Anderson, therefore addresses the issue of Justice McHugh�s, when he said to Justice Kirby, his colleague on the bench: Are we to interpret history or are we to rewrite it? We find this absolutely unpalatable, because it is their duty, as men of the High Court, to rule on matters of constitutional law, not to interpret and rewrite history for the sake of avoiding land reform and justice for Aboriginal Peoples. Their decision was influenced by a political persuasion and the desire to maintain the status quo.

This case now means that in excess of 45 000 Aboriginal people have no possibility of having any court in Australia to recognize their rights to land through the Native Title process. The current trend of the evolving state of laws in respect to Native Title is one that has seen a sure erosion of Aboriginal Peoples� Native Title rights and interests.

It is no wonder the Federal government calls �significant outcomes under the Native Title Act�, when they cite two west Australian cases concluded by consent determinations. In fact, the Federal Australian government is encouraging State and Territory governments to find some common grounds on which to enter into consensual determinations of Native Title where ever possible. We would like to emphasise that going through this process severely restricts Native Title rights and interest and it places Aboriginal Peoples in a much weaker position when it comes to bargaining power. We argue this because it is our experience that State governments and Territory authorities continually impress upon the Aboriginal parties that this is a good will gesture on the part of their governments. They fear that the continual erosion of Native Title rights and interests by the courts highlights to the world that the Howard government�s 1998 �bucket loads of extinguishment� is absolutely successful.

For our part, Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) presently entered into by the different parties are without a basis of equity. In some cases Aboriginal people say they are not happy with them, but have been told it is the best they can ever expect.

To put it mildly, a lot of Aboriginal people think they have been cheated without any possibility of redress. There is evidence of ILUAs being entered into without the involvement of all interested parties. These ILUAs are classified documents, which serve to deny the broader nation members to study and consider what was agreed to on their behalf without their knowledge. This is an absolute act of betrayal of trust. This act is neither just, nor moral.

The Federal government�s budget allocations for Native Title are well below that which can make it an efficient operating process. We submit that it is wrong for the Federal government not to fund the different States and Territories on a per capita basis, which will ensure parity of funds for the Native Title process. It is our summation that this disproportional funding between the States and Territories is influenced largely by the way different courts have ruled.

It can be concluded from this that the southeastern Aboriginal people, who have the longest association with the white Australian community, have their Native Title rights and interests severely compromised because, in these areas, they will have a greater impact upon white interest and industry. We submit in our conclusion that the Native Title Amendment Act of 1998 specifically targeted this developing conflict, so as to ensure that non-Aborigines gained the greater right, without the Federal State and Territory governments from having to make reasonable amounts of compensation.

In order to facilitate this it was essential for the Federal government to successfully introduce, within the 1998 amendments to the Native Title Act, the suspension the Racial Discrimination Act from being applicable. Thus lead to a winding back of rights and interests, in order for the courts to be at ease with their decisions. We argue that this is racist in the extreme.

Had it not been for a brief examination of the Australian Constitution Section 51 subsection xxvi by Justice Kirby of the High Court in the Katinyteri case, we would never have learned that the Commonwealth government, when passing laws for any race it deemed necessary, need not necessarily be laws for the benefit of any racial or ethnic group living within Australia. Instead, Justice Kirby warns that a Federal government, under this constitution has the power to pass laws that could be deemed to be detrimental to any race. This ambiguity in the Australian constitution poses a great threat for not just Aboriginal Peoples, but also for other racial or ethnic minorities living within our country.

On the question of Federal, State and Territory governments acknowledging and making concessions for Aboriginal traditional rights and interests, they publicly boast about transferring National Parks back to traditional owners. What they don�t tell the international community, however, is what their motives are. It is our submission that they practice a feel-good act, which lacks any Respect and sincerity for the Aboriginal Peoples. We conclude that the divestment of National Parks to Aboriginal people is conditional on them signing back the lands to the government in perpetuity.

The funding constraints for the Native Title process in NSW does not provide for any expeditious lodgment of claims on behalf of the nation. For our part, the Euahlayi People, this has seen the death of all our elders, who were the last people to have had direct contact with their grandparents, and could talk of that which existed before the coming of the whiteman and the impact of the whiteman�s arrival. Furthermore, their experience and knowledge added weight to the maintenance of traditional ceremonial practices and the observances of traditional customary law. Their ages, upon their death in 2001, 2002 and 2004 were 97, 87 and 85. More recently two other Elders have since died. Their ages were in the mid and late seventies. It is a sad reflection on the part of the courts that any evidence that we have collected from these people cannot be submitted as part of the evidentiary process, only because it was not done by court order through the Native Title Act.

For the largest proportion of Aboriginal Peoples throughout Australia, the Native Title Act has one legal ambiguity that acts as a trigger to deny due process. In the above paragraphs we speak of the authorization process. The recognition of Native Title, according to the Mabo decision, is based on custom and tradition and the maintenance of traditional law as it was at the time of invasion.

One aspect of the 1993 Native Title Act as amended in 1998, which has been thoroughly researched is section 61, which deals with authorisation of claims.

In his AIATSIS paper, Daniel Lavers correctly concludes, though inference, that the courts are corrupting Aboriginal Law, custom and tradition, because of this legal ambiguity. That is, under Aboriginal custom and Law, Aboriginal people live in �clan� units, whose territories are divided into clan estates. Each totemic clan makes decisions for those lands and no other person outside of the clan group are permitted to make decisions on matters relating to these clan estates. It is therefore incorrect for the courts to conclude that in order for Aboriginal clan groups to lay claim to, or deal with, the land they have totemic links with, they must have the approval of the other clans groups, who make up the single nation. This process is in violation of Aboriginal traditional customary Law/Lore and for the Native Title Act to prescribe this process for the courts to follow is repugnant and dictatorial. This cannot stand as a legal norm, because no judicial decision based on this distortion can be justified. No Native Title through the court process can be justified as being legally sound and correct if the reason for judgment is legally flawed. Therefore, it should not legally stand.

It is the concluded opinion that the courts in Australia are no longer considering the issue of Aboriginal custom, tradition and Law/Lore as they relate to the lands and waters under claim. It is our argument that the courts are too intent on looking at the question of the �validation provisions� within the NTA as amended in 1998. We are satisfied with the Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission (HREOC) discussion on this, under Section 2:6(1) of their submission to CERD 2005. It satisfactorily describes the problems as they have arisen through the evolution of recently determined law. We conclude, however, that the amendments to the NTA in 1998 have effectively created a regime that denies any flexibility for the court to interpret Native Title rights and interests in favour of a very clearly defined statutory rules, which govern what is to be considered are native title rights and interests. Moreover, the amended NTA of 1998 provided for a much broader base for small acts done, in relation to land, to be considered to have extinguished Native Title. Again we refer to the HREOC report where this matter is fleshed out in more detail.

The rules of evidence that emerge under the amended NTA create an insurmountable task on the part of the Aboriginal claimants and the HREOC report advances discussion on this issue.

CERD Committee criticisms of amended Native Title Act 1993 (Cth)

[Paras 117-133]

Australia�s public condemnation of the CERD�s criticism of the amended Native Title Act of 1993 was distasteful and without foundation. Aboriginal people were shocked at the public campaign conducted by the Australian government against the UN Human Rights Commission, in particular CERD. Within Australia, the print and audiovisual media coverage was emphatically in support of the Howard government�s condemnation of the UN�s procedures. We now have great concern for our rights and interests given the outcome of the last Federal election. The Howard conservative coalition government will hold absolute majority in both Houses of Parliament from 1 July 2005. We find it unpalatable that this situation has arisen, because we fear of a possibility that our rights and interest as Aboriginal Peoples will be further eroded through this new government. There now exists the potential for the Howard government to become more dictatorial about how it wants things done. The Federal government has recently sacked the only elected Aboriginal body in Australia, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC). They have now appointed their own nominees to the newly-formed National Indigenous Council (NIC) which will give them the advice that they want. This is a far cry from a democratic process. Are we to understand that in Australia true democratic processes only apply to the dominant non-Aboriginal society?

We should note that, in Australia, a further deterioration of our rights and interests as Aboriginal Peoples will exacerbate the mental trauma, grief and loss already being suffered by Aboriginal peoples throughout Australia. The present mainstreaming of the once specifically targeted programmes for Aboriginal People brings back dreaded memories of a past, where we had to live through a process of forced assimilation, including planned eugenics through specifically designed social engineering programmes.

The mainstreaming of Aboriginal identified programmes is now to be headed by a white bureaucracy and the uncertainty of Native Title and our continuing customs and traditions gives rise to violations under the Genocide Convention. As Aboriginal people we can be certain that any complaint on our part of genocidal practices under a dictatorship of Howard government will fall on deaf ears, because the only person under the Australian genocide law (International Criminal Court Consequential Amendments Act 2002) who can take a case to International Criminal Court is the Federal Attorney General. Even a public out cry cannot cause any independent inquiry. This is in breach of the Genocide Convention.

Indigenous criminal justice

[Paras 134-164]

The matter of �law and order� has become a major concern for Aboriginal communities. Since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody we now have a greater number of Aboriginal deaths in custody. Furthermore, we have various State governments choosing to build prisons and juvenile detention centres closer to Aboriginal communities. The interpretation by police of different misdemeanors are being used in a more aggressive manner and the laws protecting property are much more paramount. Ironically, since the Mabo judgment Aboriginal people being imprisoned have been charged more than ever with offences against real property and property related matters. The dominant non-Aboriginal society is being influenced through media propaganda to push for the white controlled parliaments to make more demanding laws and to set rules for curfews, which restrict Aboriginal youth from white areas and within townships. The curfews as we know them are, in our case, implemented from 6pm. Hotels in country New South Wales, where there is a preponderance of Aboriginal people, close their doors by 8pm at the latest. The rest of the population, including �acceptable� Aboriginal people, attend registered and licensed clubs, where membership is restricted to people of acceptability. This has created an environment where Aboriginal people resort to purchasing large amounts of liquor, which they take back to their homes and consume in the presence of children. It is clear to us that this is a more acceptable practice to whites, as opposed to allowing hotels to remain open in the townships and business centres.

The increased level and aggressive police practices is reflected in the high incarceration statistics that have been included in other NGO submissions to CERD.

ADDITIONAL MATTERS NOT ADDRESSED IN THE GOVERNMENT REPORT TO CERD 2005 are the effects of the Native Title Amendment Act on such matters as religious freedom and the sacred lands.

It is most unfortunate that we, in Australia, find ourselves being confronted with a most devastating practice of aggression. The aggression referred to is the low priorities accorded to our ancient religious beliefs and practices. The early ethnographers and men of pseudo science looked upon Aboriginal people as people living in total disarray and wandering aimlessly around the country searching for food for survival with no real apparent aim or purpose in life. It is only now that people have come to realize that our societies are extremely complexly organized with every detail of the peoples� lives being placed in order. They now recognize that our belief systems and practices are highly religious by design and purpose. It seems that it is our misfortune that our religious beliefs belong to the natural creation, where all things created belong to each other through an extremely intricate network of kinship relations. It is our duty as the children of the creation to maintain order to protect us the prophesies of doom, which destroyed the original creation before the beginning of time, The one we call the Dreaming. When the modern creation occurred (our present era) our creators created a set of special laws that we have to follow and adhere to without question. The coming of the whiteman and his proprietary rules of law are at direct odds with our Supreme Creators� purpose.